Updated May 2024

You might’ve heard of a little city on the northeastern coast of Italy — a beautiful city suspended on water, decorated by architecture that tells the tale of a mighty empire and the flourishing artistic scene of a bygone era.

Venice, the capital of the Veneto region, is an attraction like no other. It is made up of about a hundred small islands in a lagoon atop the Adriatic Sea, so the best way to get across is by canal. The sheer uniqueness of Venice has made it the romantic backdrop that it is today, and its beauty is an excellent complement to the remarkable history that the city has experienced too.

We’ve outlined some of our favorite destinations to see in Venice for their historical significance and fascinating roles in making the city what it is today. If you're on the hunt for local food recommendations during your stay, use the Venice Food Audio Guide for an insider's tips and favorite local recommendations. From art you need to experience to dishes to taste and eclectic neighborhoods to explore, you can start with Context.

1. Rialto Bridge

Our knowledgeable expert Matteo Gabrielli gave us the lowdown on all things Rialto, so you can know before you go.

Curving across the Grand Canal in all of its stone glory is the historic Rialto Bridge, the oldest bridge to cross the canal. It is the oldest bridge of the four noteworthy ones in Venice. Since the 12th century, it has been built and rebuilt a number of times.

Nicolò Barattieri first laid the groundwork for this beautiful structure in 1178 when it was a wooden pontoon walkway meant to connect the two sides of the canal. At first, it was made of old shallow boats to support people walking across it. To make it more supportive, the pontoon was made into a wooden drawbridge. But like many wooden structures in history, it caught aflame during the Great Fire of Rialto in 1514. In 1588, Antonio da Ponte began its transformation into the stone arch bridge it is today.

What you'll see at Rialto Bridge

Part of Rialto Bridge’s allure comes from its symmetry. Both sides of its arch are almost exactly the same. The tall and wide arch is surmounted by a low parapet, a protective wall along the edge of the bridge. There are also lines of shops above the white-gray walkway.

When you’re on the bridge, you’ll want to head to the southern part. While it’s often crowded, this side has the best view of Venice and the Grand Canal. You can avoid the crowds by getting to the bridge in the early hours of the morning. Reward yourself with a delicious breakfast in the Rialto Market afterwards!

2. Rialto Market

For centuries, the Rialto Market area had been the economic center of Venice. The historical roots of the market span back when the little island was first settled by early Venetians. Back then it was called Rivoaltus.

By the 11th century, the area had already become the town’s central marketplace. Merchant goods were loaded and unloaded onto boats coming across the Grand Canal. Eventually, it made sense to connect these two waterfronts with a bridge — the Rialto Bridge!

This market originally sold vegetables, fruit, cheeses, meats, fish, expensive spices from the East, metal, precious stones, silk, and other luxury items. To this day, these divisions are still recognized. The area is organized by the produce stands and goods that had previously existed through history.

What you'll see at Rialto Market

The city is surrounded by water, so it isn’t too surprising that there was a large, prominent fish market in Rialto Market. Fun fact: there used to be an official fish person that determined the freshness, quality, and size of the fish before they were sold. Years later, there is still a white marble board that specifies the minimum size of a fish before it can be sold.

If you go to Rialto Market, be sure to beat the rush by going early. Buy fresh produce, spices, and wine for an aromatic, crisp meal. You can take a tour of the Rialto Market with us through the market and sample the local specialities with a local chef, food writer, or foodie. Learn about the special cuisines of Venice like schie, tiny shrimp from the lagoon, ciccetti, Venetian snacks, ombra, a small glass of wine, and so much more! And if you want to savor the wines of Venice, be sure to check out our Venetian Wine Tasting Tour tour.

3. St. Mark's Square

Piazza San Marco, or St. Mark’s Square, has been an important meeting place for Venetians and tourists throughout time. Napoleon once referred to St. Mark’s Square as the “Drawing Room of Europe” most likely because of its wonderful tranquility as you sit and observe your surroundings. Like the regal Basilica, the impressive square was meant to show off the city’s wealth, especially if one comes from the direction of the water.

The Square represents all forms of public life with its political, religious, historical, and intellectual buildings like the St. Mark’s Basilica, St. Mark’s Bell Tower, Doge’s Palace, the National Library of St. Mark, the National Archaeological Museum, the Museo Correr, and the many outdoor cafes.

For an in-depth exploration of everything this area has to offer, use our St. Mark's Square Audio Guide (narrated by a Context expert) for a deep dive into the history, architecture, and art of several iconic venues.

What you'll see at St. Mark's Square

St. Mark’s Square used to be paved with terracotta blocks, but that material was replaced by stone in 1735. You’ll see two 12th century columns on the waterfront with the statues of both patron saints of Venice: Saint Mark in the form of a winged lion (who you can also see on the large facade of St. Mark’s Basilica) and Saint Teodoro. We’ll dive deeper into some of the important places in this square below.

4. Saint Mark's Basilica

Begun in 829, St. Mark’s Basilica is one of the oldest, most renowned buildings in Venice. Did you know that the origins of the basilica involve thievery? Not exactly the holy beginnings you’d think! As the story goes, St. Mark’s Basilica was built to house stolen relics from Alexandria, Egypt.

Venetian merchants robbed the body of St. Mark the Evangelist, one of the four Apostles to keep him in the city. The thieves almost died at sea bringing their precious cargo back, but, as the legend goes, St. Mark himself told the captain to lower the sails for safety. You can see the tale illustrated on the 13th century mosaic above the door as you enter the grand space.

The church, like many historical landmarks, was burned, restored, and renovated countless times. The first iteration was burned in 976 as an act of defiance against the doge Pietro Candiano IV. The Basilica as it stands now was completed sometime between 1063 and 1094 under his successor, Doge Domenico Contarini.

Crowned by five domes in the Greek-cross plan, the design is in the Byzantine style and has been renovated throughout history to represent the richness of Venice. Its opulent decor, rich interiors, and magnificent facades were added in the course of a couple centuries. According to Matteo, after the sack of Constantinople and the Fourth Crusade, much of the treasures were sent to St. Mark’s Basilica like polychrome stones, four bronze horses, enamels of the Golden Altar-piece, and much more. Venice had to especially show off its wealthy power once it became a maritime power with the military occupation of Greek and Turkish islands in the 13th century. The expensive marbles, sculptures, ceremonial objects, and golden mosaics do a good job of boasting Venetian lavishness. It’s no wonder that St. Mark’s Basilica became a treasure chest for war looters!

What you'll see at Saint Mark's Basilica

There’s so much to look out for in this grand basilica, but you might want to start out with the wonderful facades, a mix of smooth marble slabs, colorful columns and mosaics with a golden background. If you turn your head to the largest facade, you’ll see the four bronze horses from Constantinople. On the top of those bold horses, you’ll see an imposing golden lion with wings overlooking the square, the patron saint of Venice in the form of an animal. As you enter, you’ll stare in awe as you observe the shift from natural light to the light reflected by thousands of glittering tiles.

Would you believe that’s only the beginning? In fact, there are enough mosaics in St. Mark’s Basilica to cover one and a half football fields! See it in-depth, and learn so much more about the ornate basilica with an expert on our Introduction to Venice tour.

5. St. Mark's Bell Tower

Many of history’s relics have been subject to building and rebuilding and St. Mark’s Bell Tower is no different. The Campanile di San Marco is the bell tower of St. Mark’s Basilica, and is one of the most recognizable representations of Venice. It was originally built as a watchtower to catch ships approaching Venice and to protect the city.

The construction began in the twelfth century and was completed in the 16th century with a spire and belfry. In addition to signifying religious services and holidays, the bells also regulated public life by ringing at the beginning and end of a workday, indicating political happenings, and marking public executions.

Another claim to fame for this remarkable site is that Galileo Galilei introduced his telescope to Doge Leonardo Donato and his Senate at the top of the bell tower! Learn more about Galileo in Venice with the kids during our Doge's Palace Tour for Kids: Galileo in Venice tour.

On July 14th, 1902, St. Mark’s Bell Tower collapsed due to an unstable foundation. Architects were working on renovating parts of the tower when a large crack split its way along the northern part of the tower, a crack that deepened in the subsequent days. People were ordered to evacuate the St. Mark’s Square, so no one was hurt, and nearby buildings were also relatively unharmed. The only fatality, unfortunately, was the custodian’s cat.

While the collapse of the St. Mark’s Bell Tower was a national tragedy, the country acted quickly to rebuild it. Within ten years, the historical bell tower was restored to its former glory in 1908.

6. Doge’s Palace

One of the most iconic buildings in Venice, Doge’s Palace holds a very important role in Venetian culture because it was where politics and government in the city were run. From about 726 to 1797, doges ruled Venice. Doge, often referred to as the Serenissima, were elected officials who held office for life, but could not pass down the title to his successive heirs.

Choosing a doge was not always a clear-cut process. Usually, they would be chosen from an inner circle of trusted and powerful Venetian families, so while there was a law that ensured the title could not be passed down within the family, there was a level of nepotism that still existed.

What you'll see at Doge's Palace

Touring the Ducal Palace is key to understanding the history of the Venetian Republic. Like St. Mark’s Basilica, the building itself, both inside and out, were strategically designed to reflect the status of the aristocracy and the wealth of Venice to other major world players, especially once the city became the center of trade and commerce in the 13th century.

The architecture of the palace is uniquely Venetian with its influences in Gothic, Byzantine, and Late-Renaissance styles. Patterned with pink Verona marble and white Istrian stone, Doge’s Palace captures the wealth of the Venetian empire at the time of construction, an empire that could easily import riches from different parts of Europe.

Let’s take you along some of this palace’s riches with our expert Sara Grinzato. She says, “As soon as the visitor enters the palace, one is struck by the spacious courtyard that unexpectedly opens up before his/her eyes.” The courtyard, as lavish as it is, is actually not as harmonious as it presents itself to be. You’ll see two wings of the palace in different styles — one in Late Renaissance and one in Gothic. In this courtyard, you’ll spot the massive statues of Mars and Neptune commissioned to the celebrated architect Jacopo Sansovino.

Passing the courtyard, you’ll go up the Scala d’oro, the golden (yes, real gold) staircase designed in 1550. On top of these stairs, you’ll find rooms where councils of the state met.

Two rooms of note that you can’t miss: the Council of Ten room and the Scrigno Room.

- The Council of Ten, or the Consiglio dei Dieci, were a powerful group of ten judges who assessed the most notorious crimes of Venice. This elite group was established after Bajamonte Tiepolo tried to overthrow the state with some other noblemen.

- In the Scrigno Room, there is a silver book that took note of all families of the royal echelon. These records supported Venice’s stringent class system that forbade marriages between the upper caste and the everyday people. The documents that secured legitimacy for these royal families are in a chest in the Scrigno Room.

In addition to the world-renowned paintings by Renaissance legends Tintoretto and Titian, you’ll be interested in the Doge prisons. The prisons inside Doge Palace itself, Piombi and Pozzi, were not big enough to house all the prisoners, so the aristocracy later built the New Prison House that remained in use until the 1920s.

Need more of an expert-driven deep-dive into Doge's Palace? Hop on a tour with Sara Grinzato herself and learn all you need to know about this poetry-inspiring Palace.

7. Bridge of Sighs

Venice expert Matteo Gabrielli tells us that the location of this limestone bridge spanning across Rio di Palazzo is pivotal to its story. In between the Doge Palace and the prisons, the Bridge of Sighs is the only bridge in Venice that is completely enclosed. Any guesses as to why?

This design was meant to prevent anyone, namely prisoners, from jumping into the canal. Similarly, it was named for the prisoners sighing as they passed through the enclosed bridge, glimpsing their last view of freedom outside the window, before heading into the cells.

However, the Bridge of Sighs had a slightly different name when first built. Antonio Contino, who also executed the nearby prisons (the Palazzo delle Prigioni), built the beautiful bridge in the early 17th century century with a very straightforward name: The Bridge of the Prisons.

Contino was commissioned by the doge Marino Grimani who wanted his coat of arms illustrated in the center of the bridge. With its elaborate Baroque style and royal emblems, you’d never guess that the Bridge of Sighs had such sad origins. In fact, it’s tradition that a couple who kisses under the bridge will experience eternal love! Perhaps the people of Venice didn’t want to be reminded of the depressing matters above as they floated underneath the magnificent bridge.

What you'll see at the Bridge of Sighs

As an insider tip, Matteo recommends observing the Bridge of Sighs from the Ponte della Paglia, the bridge that connects St. Mark’s Square to the Riva degli Schiavoni, the long Southern waterfront of Venice. A disclaimer, however, is that it is the most photographed bridge in Venice, so the Ponte della Paglia is often crowded with tourists. If you’re determined to see the best angle, you’ll need a bit of patience! Follow the itinerary through Doge’s Palace if you want to cross the bridge too.

8. Jewish Ghetto

Vividly depicted in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, the Floating City had a thriving community of Jewish people in the Cannaregio neighborhood. We highly recommend exploring the deep history of Jewish life in Venice. Matteo explains to us that the Jewish Ghetto of Venice was created by the Senate of the Republic on March 29th 1516.

Venice’s Jewish Ghetto was the first ghetto of human history. The etymology of the term “ghetto” derives from the Venetian word, ghèto, which was a foundry for copper. Before the arrival of the Jewish population in Venice, Cannaregio, the district where Jews were confined, was known for its metal foundry. Thus, the word “ghetto” was born — a restricted place where Jewish people could live.

Before the creation of the Jewish Ghetto, Jewish merchants could do their jobs in the city, but they could not live in Venice. With the Senate of the Republic’s decision, Jews were allowed permanent residence only in the neighborhood, and they had to distinguish themselves with a yellow hat or badge so they weren’t confused with the Christians. Jewish doctors, allowed to wear black hats, were the only ones exempt from this rule since they were in high demand. The gates of the Jewish Ghetto were closed at night as well, locking the community inside the district.

In spite of the harsh conditions of ghettoizing, the community here grew and began building synagogues. Since those who lived in the Ghetto came from Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and other parts of Europe, the area became a flourishing cultural hub. It became an important place for communities and intellectuals to come together. Poets, artists, merchants, and Christans and non-Christians alike would gather and exchange ideas. The Ghetto stands as a testament to Jewish culture and resilience through history.

What you'll see at the Jewish Ghetto

When you’re there, you’ll see the three Ghettos: Ghetto Nuovo (New), Ghetto Vecchio (Old) and Nuovissimo (Newest). You’ll have to visit the three synagogues in Ghetto Nuovo and the two in Ghetto Vecchio. A heads up — the three in Ghetto Nuovo might be hard to spot since they are concealed inside buildings, but the two in Ghetto Vecchio have more imposing facades and should be easier to see.

One last tip: if you’re looking for a snack, look for the local Jewish bakery and try their cookies!

9. Grand Canal

Perhaps the most famous and notable canal in the world, the Grand Canal is as historically important as it is beautiful to look at. Gazing at this remarkable waterway, it’s easy to see why the likes of Hemingway, Byron, James, and many others were inspired to write about it. People have known of its significance long before the Romans came as well. Civilizations lived along its banks in stilt houses, relying on fish and salt for sustenance, both economically and personally.

What you'll see at the Grand Canal

The Grand Canal follows a natural reverse S-shape from the San Marco Basilica to the Santa Chiara Church and divides the city in two parts. While crucial to the Floating City’s identity, it’s not actually that long. It’s only 2.36 miles long! What it lacks in length, it might make up for in depth at 16.5 feet, although we don’t recommend swimming in it. The canal carries every type of transportation, so it might be dangerous! Cargo, public-transit waterbuses, gondolas, emergency siren-boats that belong to police and medical institutions, and other vehicles traverse the canal every day.

To connect both sides of the Grand Canal, there are four bridges to look out for:

- The Rialto Bridge

- The Accademia Bridge

- The Scalzi Bridge

- The Constitution Bridge

No trip to Venice is complete without a boat ride down this ancient waterway. We’ll introduce you to the different Venetian neighborhoods, guide you through historic sites, and situate you in the city during our Venice by Boat: Grand Canal Tour.

10. Venice Art: Accademia Gallery

Your trip would be absolutely remiss if you didn’t take a gander through the prestigious art institutions of Venice. Venice was a significant contributor to art, architecture, and sculpture during the Renaissance. The artistic history of the city is as important, and in many cases a part of, its political and economic history.

The Accademia Gallery holds the world’s greatest collection of Venetian paintings. According to our expert art historian in Venice, Susan Steer, many of its paintings came from defunct Venetian institutions after the fall of the Republic of Venice. They represent the salvation of Venice’s material culture during the city’s darkest period. There’s so much Venetian culture to absorb, but most exciting paintings are masterpieces by the greatest Venetian artists. You’ll have the pleasure of seeing Giovanni and Gentile Bellini, Carpaccio, Giorgione, Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese, and many more.

What you'll see at the Accademia Gallery

The Accademia Gallery is housed in a historic complex that used to be the first buildings of Venice’s lay society. This complex includes the Scuola Grande della Carità (Great School of Charity), which was a 13th century school established by the Church of San Leonardo, and the adjacent monastery. Original features of this complex include two spectacular fifteenth-century ceilings, as well as paintings made by prominent artists for the lay society, including Titian’s Presentation of the Virgin.

If you need somewhere to start, here are some key works to look out for:

- Justice and the Archangels painted in 1421 by Jacobello del Fiore. Painted for the offices in Doge Palace, this triptych was most likely conceived to mark Venice’s legendary 1000th birthday. It’s pretty incredible that this work even exists to this day. The masterpiece narrowly escaped the major fires that consumed Doge’s Palace in the 15th and 16th centuries.

- Gentile Bellini’s Procession in St Mark’s Square is a large canvas that depicts Venice’s most famous square as it was in 1496. This painting was commissioned as a series to depict the miracles of the True Cross. Here, Bellini portrayed an event that took place fifty years prior — a tradesman from Brescia, Jacopo de’ Salis, who prayed to the cross that his dying son might recover. He came home to the boy completely recovered.

- Part of the same series, Carpaccio’s Miracle at Rialto Bridge shows the arched bridge over the Grand Canal when it was still a rickety wooden structure, long before the magnificent stone bridge we see today. You can see the barebones of the bridge today, two points converging together like top sides of an isosceles triangle. This painting in the series depicts the healing of a madman by the True Cross relic.

- Painted in 1548, Miracle of the Slave was the first important commission to be won by Jacopo Tintoretto, and it is a tour de force — the artist proved that he could master difficult techniques like foreshortening and perspective. You can see the artist’s talent in the extraordinary energy and dazzling brushwork of the painting.

- Veronese’s Feast in the House of Levi by Paolo Veronese is an enormous and sumptuous feast scene, which had originally been conceived as a Last Supper for a monastic dining room. The lavish detailing and extraneous characters — including “drunks and clowns” — prompted the attention of the Holy Inquisition, and the artist had to defend his work before the inquisitors. Paolo Veronese was the first recorded artist to defend his artistic freedom.

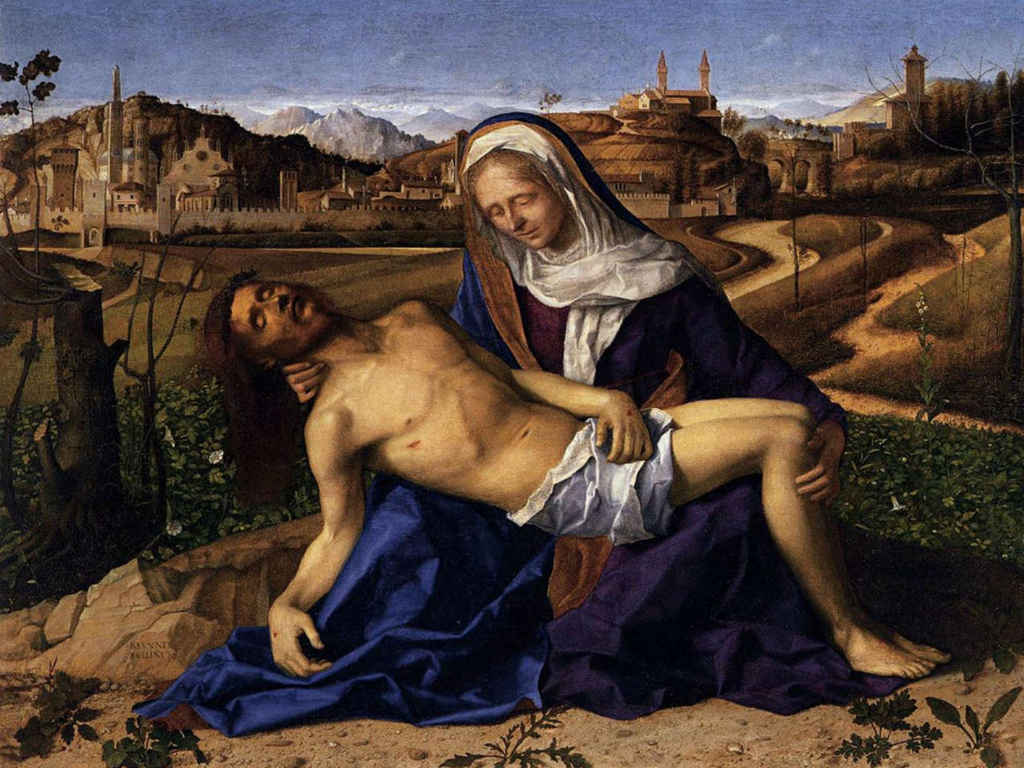

- Celebrated master Titian painted the renowned Pieta when he was over ninety years of age! Although Titian had reached unprecedented international fame and great wealth, this late pieceis filled with humility. This was fitting since the artist intended to place this painting above his own grave in the great church of the Frari.

If you’re curious about more Renaissance art at the Accademia Gallery, join Context expert Susan Steer in-person for a private, holistic guide of the Accademia Gallery and more art around Venice.

11. Murano Island - Murano Glass Museum

Venice has had an incredible history of glass making since the middle ages. This history has had a huge role in Venetian commerce that can’t go unnoticed. The island of Murano is home to the city’s glass factories and artisans. During our Half-Day Tour of Murano with Private Boat Transfer, you’ll learn all about how the craft has evolved, and you’ll discover what makes Murano glass so unique. For now, we’ll give you a brief introduction to this distinctive history.

While Venetians didn’t actually invent glass (traces of glass manufacturing was found in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia), they certainly had a hand in perfecting its art. Glass was so important to Venetian culture that there were patents protecting the inventions by glassmakers. Eventually, glassmakers became so well-regarded that they established a glassmakers guild and were considered part of the local nobility. People treated them like royalty and granted them certain special privileges. The illustrious profession became more and more popular, and by the 16th century, over half of Murano’s citizens were involved in the industry in some way.

In 1291, the Doge closed all glass factories in the mainland and relocated them to the islands outside Venice to minimize fire hazards. This was a pretty good idea since glassmaking was very conducive to fires, especially as roofs back then were made of straw. The worst fire from a glass incident was in 1105 that destroyed twenty-three neighborhoods and churches!

Both the Plague and Napoleon’s capture of the Republic of Venice forced a downturn in Venetian glassmaking. However, the interest and tradition held strong until the 20th century when glassmaking became a form of art. An influx of artists to Murano in the 1980s cemented the island as one with artistic significance.

If you’re in Murano, you can’t miss the Murano Glass Museum, which contains a fantastic collection of historic glass objects and allows you to trace the development of glass in Venice over the centuries.

12. Church and Scuola Grande of San Rocco

Not only is Susan Steer an expert in the art history of Venice, she also is very knowledgeable about Venice's connection to the Black Death. She gave us this very interesting rundown on the bubonic plague in the city. As we know, Europe was ravaged by the bubonic plague between 1348 and 1631 and Venice was no exception. The lagoon has an interesting history of the plague, which can still be seen today.

When the Black Death reached Italy, the medical community knew about the epidemic, but most believed that it was a punishment for sins. Still, Venice reacted in decisive ways and had severe guidelines on conduct (sound familiar?). One way that they ensured safety was the construction of the lazzaretto, a hospital on a confined island of the Venetian lagoon. Another way they ensured safety was establishing the quarantena (where the word quarantine comes from) rule where all passengers on ships had to be isolated for forty days before disembarking from them. Despite these measures, the plague believed to have killed 47,000 people between the outburst in 1630-1631.

In another bout of the terrible pestilence, the society, or Scuola Grande, of San Rocco was formed as a lay brotherhood in 1478, in honor of the plague saint. A few years later, their church became the shrine of the saint when his alleged remains were brought to Venice. Given Venice’s repeated plagues, the confraternity attracted a large membership and grew to be one of the most prominent common societies in the city. They became so wealthy with premises so lavish that they were criticized for squandering money on vanity projects. Following the trend of grandeur set by royalty, the Scuola Grande might not have spent enough on the charitable causes that the organization had been founded on. Their impressive buildings were decorated by the great Venetian artist Jacopo Tintoretto. Here, you can imagine how the sins of humanity were correlated with the onset of the bubonic plague.

13. Santa Maria della Salute

The Church of Santa Maria della Salute represents Venice’s spiritual response to the great plague pandemic of 1630-31, which cost tens of thousands of lives. The church was erected by decree of the Venetian Senate, and it was designed by the young architect Baldessare Longhena, who competed with other challengers to win the contract. The church is now recognized, not only as a key landmark in the city, but also as Venice’s first and greatest Baroque monument.

To this day, the church is the center of an annual festival held on the 21st of November that celebrates the end of the bubonic bout in 1630-31. Historically, on the occasion of the feast of the Presentation of the Virgin to the temple, the Senate would cross the Grand Canal in a ceremonial procession as a sign of gratitude to the Virgin Mary for liberating the city from the plague.

What you'll see at Santa Maria della Salute

This beautiful, baroque-styled domed basilica overlooks the Grand Canal. On its apex of the church’s pediment is a statue of the Virgin Mary, presiding over the city. Inside, the sacristy is definitely worth a visit since it holds important works of art by Titian and Tintoretto.

We’ve outlined 13 things to see in Venice and the historical context you need before visiting them, but we’ve only given you the tip of the iceberg. Join us on our many tours in Venice for more insights and history!

A special thank you to our Venice experts:

- Matteo Gabbrielli - take a tour with him.

- Sara Grinzato - take a tour with her.

- Susan Steer - take a tour with her.