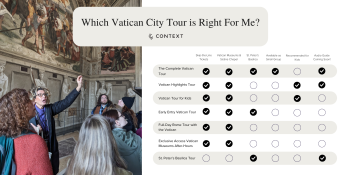

Rarely do we get tired of putting things into context (*nerd alert*), but occasionally we like to frame things a different way and put them in perspective. The master of perspective was of course Raphael, whose "School of Athens" fresco in the Vatican’s Stanza della Segnatura is widely renowned as one of the best examples of linear perspective in the annals of art history.

If Michelangelo is understood as the melancholic solitary genius, then our friend Raphael Sanzio from Urbino is of the entirely opposite type: he epitomized the artist as a man of the world whose expertise and curiosity was seemingly endless (remind you of someone?).

2020 marks the fifth centennial of Raphael's death, and there is a year of blockbuster shows ahead (the Scuderie, the National Gallery, just to name a few). With that in mind, this is an assemblage of thoughts from our Italian art historians meant to put the great Renaissance master in (linear) perspective:

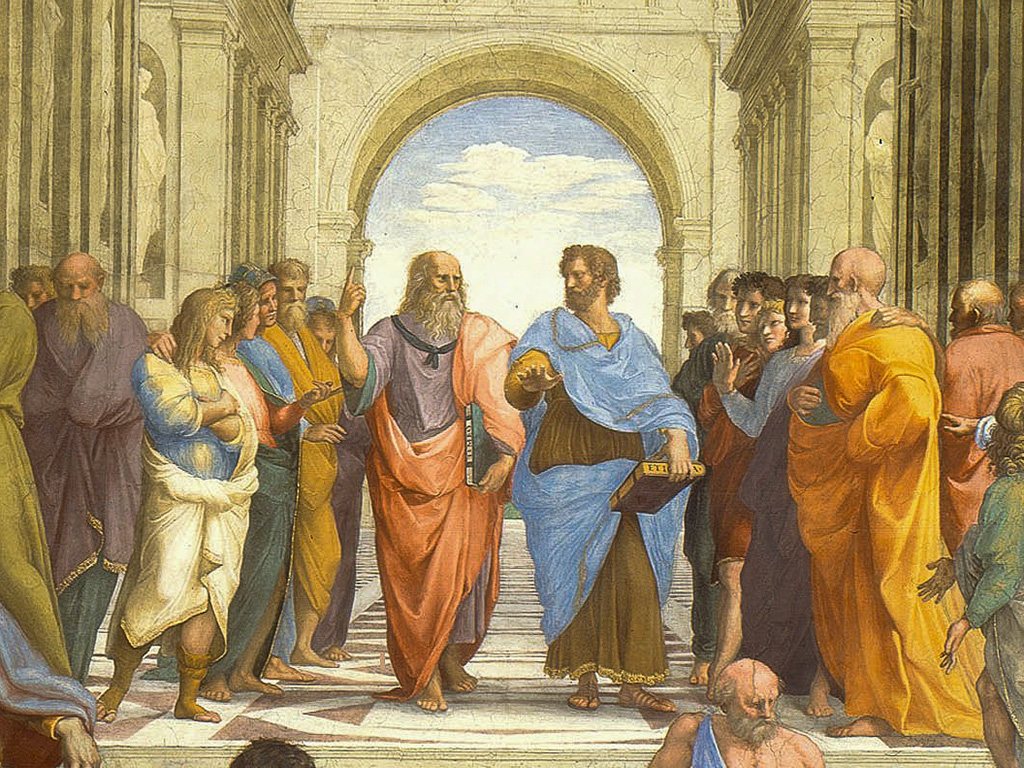

Familiar faces in the School of Athens

As its name suggests, the famed fresco features the great philosophers of classical Greece. But our guide Janet also likes to point out that many of the famous faces are actually those of Raphael’s various contemporaries. A rather well-known one is Michelangelo as a brooding Heraclitus, the pre-Socratic philosopher who propounded the doctrine of universal flux. A more subtle (but immensely important) portrait is that of the architect Bramante, dressed as the mathematician Euclid. This is where Janet urges us to squint and see that Raphael signed his name on the gold collar of Euclid’s tunic—a gesture whose full significance will be revealed below.

Timing matters, and other important lessons

Raphael was working on his fresco at the same time that Michelangelo was painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling, and our guide and art historian, Jose, emphasizes that the two were influenced by each others’ work as their projects progressed. One example is the treatment of the book that Plato is carrying in the School of Athens. Titled "Timaeus", Plato’s book tells of the story of Atlantis, a fabled continent that wrought its own downfall by pursuing technology and knowledge at the expense of ethics. Michelangelo, meanwhile, was depicting Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Paradise because of their pursuit of knowledge. Different as those two artists were, it seems they agreed on one thing: that curiosity killed the proverbial cat.

See the school of Athens and Raphael’s other frescos in the Papal apartments at the Vatican on our popular Arte Vaticana Tour. Traveling with your little artists? Hop on the Vatican for Kids tour.

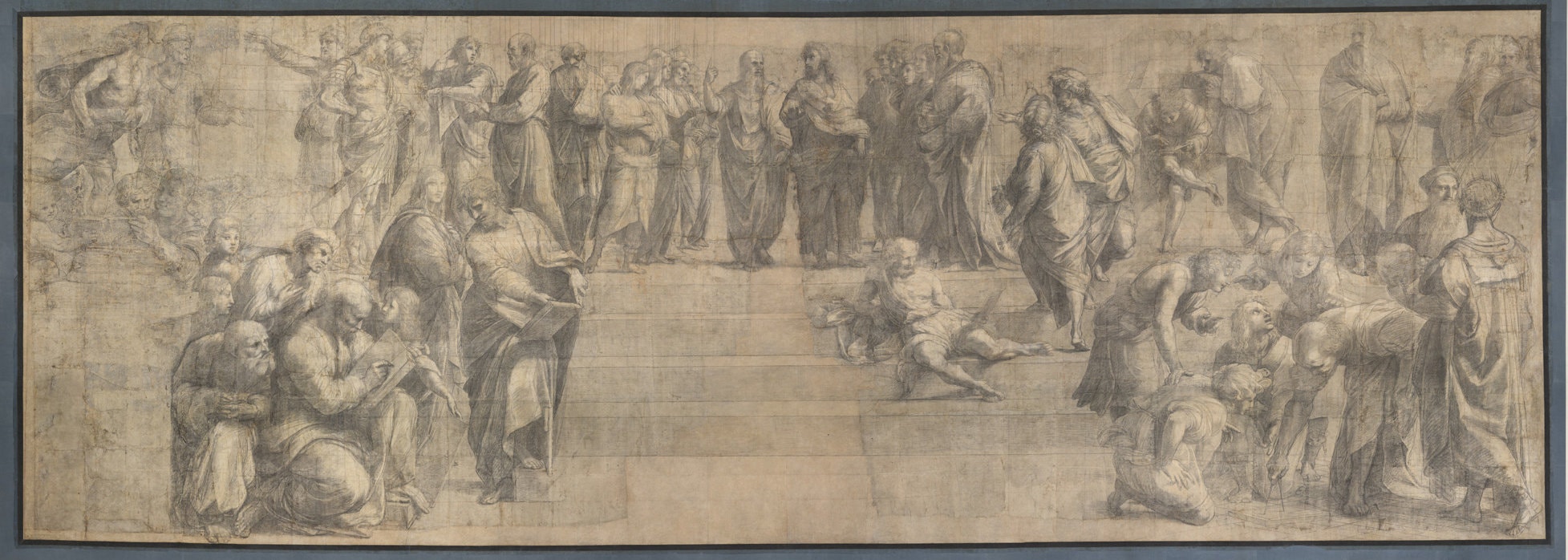

A Study in...Milan

As much we love the magnificence of a finished work of art, our guide Hilary reminds us that preparatory sketches can be even more revelatory about the artist’s intentions. These early sketches are rare: because they’re typically not produced with posterity in mind, they scarcely survive the finished commission. One magnificent exception is Raphael’s cartoon for the "School of Athens", on permanent display at Milan’s Pinacoteca Ambrosiana.

Unlike the completed fresco (executed faultlessly by Raphael and his workshop), the sketch is entirely of the master’s own hand. It’s a marvelous window into Raphael’s process and original composition plan, offering an intimate look at his technique that would otherwise be hidden by opaque layers of paint.

Keen to see Raphael's study and other Renaissance masterpieces in Milan? Hop on a custom tour with Context.

The artist-architect

Raphael is today known primarily as a painter: however, he was also a very talented—and underrated—architect. When he was called on to fresco the apartments of the pope, Raphael’s mentor (and fellow Urbinate) Bramante was the chief architect of New Saint Peter’s. Those with a keen eye will have noted that the architecture painted in School of Athens bears a striking resemblance to the interior of St. Peter’s. It was only with Bramante's death in April 1514 that Raphael’s architectural skills came to the fore: at Bramante’s dying request, Leo X promoted Raphael to Bramante's office as architect of St Peter's. As chief architect of the pope, Raphael created the design for a chapel in Sant'Eligio degli Orefici, as well as the Chigi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo.

Architecture is one medium that doesn’t translate nearly as well on paper—visit Raphael’s churches on our new Raphael in Rome: Portrait of an Artist Tour.

(For architectural historians, we always recommend taking a small detour to Bramante’s Tempietto, in the courtyard of San Pietro in Montorio. Though historians often label it as more of a sculpture than architecture, it’s a small but mighty thesis of High Renaissance architecture, lauded as one of the most harmonious buildings of the era.)

In search of beauty, in pursuit of the ideal

While Raphael’s work in the Vatican is oft considered his magnum opus, we’re partial to his mythological fresco series at the Villa Farnesina. The ceiling lunettes here depict stories from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, including the breathtaking “Galatea.” Raphael’s nod to ancient Roman literature—a typical characteristic of the broader Humanist movement in the Renaissance—and the grace and beauty of the Villa’s figures are a perfect encapsulation of his style.

Visit the Villa Farnesina with Context on our Myths for Families: Raphael and the Trastevere tour with a PhD or MA-level art historian.

A Renaissance Man with many friends

We don’t think Raphael will mind if we do some name-dropping on his behalf, so we’ll come right out and say it: Raphael was extremely well-connected in his contemporary social circles.

Raphael’s father Giovanni Santi—a great painter in his own right—made sure that the young Raphael had exposure to the greatest artists in the court of Urbino. That included Giovanni’s own teacher Piero della Francesca (known as the founder of painterly perspective), groundbreaking author Pietro Arentino, and the printer Marcantonio Raimondi. The court’s dialogues are recorded in "The Book of the Courtier" by Baldassare Castiglioni, who had his famous portrait (on-loan at the Scuderie) painted by none other than, you guessed it, Raffaello.

“Raphael could work”...

… is how Janet describes the quality that sets Raphael apart from the others in the High Renaissance trinity, Leonardo and Michelangelo. For the short years that Raphael was active, his artistic output is testament to not only his productivity but also his ability to bring works to completion (something Leonardo lacked, as evidenced from our recent visit to the Louvre’s da Vinci show). Raphael was also known for his positive relationships with his patrons (the same can’t be said for Il Divino, and our guide, Livia agrees).

To get a better idea of the volume and quality of Raphael’s artistic output, join us on our tour of the temporary exhibit, Raffaello, at the Scuderie del Quirinale, and see some of the master’s most legendary paintings on-loan from institutions around the world.

Context tours you'll want to take:

- Raphael in Rome: Portrait of an Artist

- Myths for Families: Raphael and Trastevere

- Popes, Power, and Parties: the Renaissance in Rome

- Borghese Gallery Tour

Upcoming seminars and courses you may want to take:

- Nov 6. 2021: Treasures of the Borghese Gallery with Cecilia Martini

- Nov 21, 2021: Meeting Rome's Finest Artists – Michelangelo, Raphael and More: A Five Part Course with Livia Galante

- Jan 9. 2022: Umbria, A Harmony of Art and Nature: Gubbio, Perugia and Lake Trasimeno with Kate Bolton-Porciatti

Other blog posts you may Like:

- 10 Facts about Michelangelo’s Statue of David in Florence, Italy

- Papal Crest Symbolism in Rome

- Food Culture of the Italian Renaissance

- The History of Fascist Architecture in Rome