Cadenza on Sacred History – Notes on Michelangelo's Frescoes for the Pauline Chapel

Written by: Paolo Carloni

Foreword

On the many trips to the Sistine Chapel that an art historian specializing in the 16th century humbly decided to make as a tour guide in order to gain his sou without compromise, tenaciously faithful to the idea of an existence with no shame - having the Rome Programs of the American university institutions, for which he had worked twenty years, lost their educational function under the pressure of the market and of censorship - his eyes had always fallen on the heavy wooden doors that blocked the way to the Sistine Chapel, thereby stoking the fire of curiosity as to what lay beyond it: the Pauline Chapel that holds Michelangelo's last two frescoes!

Thanks to a fortunate series of events, in May 2016 he could visit twice the most audacious painterly work of Michelangelo. The reaction to the shock he received on those two meetings took the shape of a bilingual four hundred pages book entitled "Come in uno Specchio - Through a Glass Darkly. Michelagniolo and his last two lieder for the Pauline Chapel"(Rome, 2019).

The considerations that are about to be read are the abbreviated form of some of those contained in that volume and reworked for an essay just published in the book 'Giardini di conversazione. Studies in honor of Augusto Gentili ' (Rome, March 2023) celebrating the 80th birthday of one of the greatest scholars of Venetian art.

The Power of Semblance

At the peak of his artistic career and of his own historical solitude, Michelangelo reserves the supreme right of applying his own linguistic choices without any restrictions in terms of time, genre, style; a sort of recapitulation, sometimes a juxtaposition of all of the stylistic features that preceded it in time, contemplated from the height of a transcending ‘point of view’ that makes all of them equal. Old and new, current and obsolete, dated and updated, are categories that don’t fit into this sublime ‘glance’ that knows how to revive the ruins of a past that for others is irreversible, and to reactivate them not as inert citations but rather as constitutive element that has been reinvested with intrinsic necessity.

The complexity and unprecedented novelty of this choice is the primary cause of the amazement of the contemporaries and of the irritated, superficial and careless (in)comprehension of posterity.

Michelangelo, as if he wanted to give eyes to the blind and speak to the deaf, had re-invented Mannerism in his Last Judgment, with the ultra-refined postures of the bodies, with their exaggerated spiralling rotations and heavy anatomic plasticism, in a personal research of the ideal and tragic beauty by then totally separated from the classic manner. With the Last Judgment, he shoots Mannerism through the sound barrier.

The frescoes of the Pauline Chapel, located just a few metres away from the Last Judgment, are the requiem of Mannerism; they recite its eulogy, leaving it to melt in the Lethe of the new combination of delicate colour without discord, blended with the suspended non-plastic monumentality of the body shapes. The most unexpected ‘wiping of the slate’ in the history of art before Picasso: the Mannerist school and the very recent past of the Last Judgment wiped out under the Gorgon's eye of extraneousness.

Every work of art - including Michelangelo’s ‘inspired’ works - is a historical fact, namely an event that cannot be ignored and that changes the course of history with the power of happening, that in art is the power of semblance. The same power that subjugated the scholar who lost his bearings at the sight of these two frescoes in a place inaccessible to most common mortals.

Now, which tools does the art historian possess in his attempt to comprehend the meaning of Michelangelo’s work in the Pauline Chapel, if not the very art of Michelangelo tout court?

In summarizing the last one hundred years of history of art, one may say that they have been dominated by two main schools of thought, that I call Capriccio (Fancy) and Catasto (Inventory).

Capriccio has expressed itself via more or less fanciful ‘nursery rhymes’ about the style of the various artists and about the effects they generate in the scholar, in an offhandedly subjective manner in which the work of art is only an excuse, an insignificant detail and not a significant one and thus never looked at with serious attention and ultimately superfluous.

This is the ‘school’ that enunciated nonsense about Michelangelo’s painting style, prior to the restorations of his sistine ceiling, when pages upon pages were written about the absence of colour ‘typical’ of the Florentine school or about the powerful chiaroscuro of certain figures, when instead it wasn’t the frescoes’original paint colour at all but only vulgar glues added on in the 18th and 19th centuries!

Catasto is more objective, aiming at the contents, based on research in archives, on the reconstruction of the clientele, basically following the rule of good old American journalism anticipated by Kipling in his poem Six Honest Serving Men, named What and Why and When and How and Where and Why! But the myopic lack of imagination of Inventory, obsessed as it is with facts, is none other than the opposite face of the projective unleashings of Capriccio.

If one would assign Capriccio to the world of hysteric-psychotic dysfunctions, Catasto would fall into the neurotic compulsion category.

The urgent question still remains: is Michelangelo’s Pauline Chapel something that can patiently await an interpretation without being consumed by its own aura?

The retrospective attitude of the traditional historical method is reductive, and when it comes to the history of images, it is also false, because they are presence! To ‘represent’ means to present again. The statute of the image that occurs under our very eyes ‘here and now’ means that the scholar who looked upon these two frescoes was impressed, struck, shocked and wounded by them, and therefore reached and touched, and the scholar’s words must evoke this ‘being impressed’ that occurs in the present and projects into the future. This is the enigma of iconicity.

Privileging the present is Michelangelo’s own attitude, seeing the experience of the present lived as eternity, conceived as a nunc stans, an eternal present. He is aware of the dialectics regarding the temporality in his works, and he remembers the tria tempora of his Augustine readings, the knowledge of which arrived to him directly through the Augustine's writings but also via the study of the works of Petrarch, whose primary role in Michelangelo’s art was underlined for the first time by the author of this essay in 2010.

Augustine had made the present explode into three directions: the present of past things is memory; the present of future things is expectation; the present of present things is vision. To Michelangelo, painting is then the visualisation of these tria tempora: the vault of the Sistine Chapel or of memory; the Last Judgement or of expectation; the Pauline Chapel or of vision.

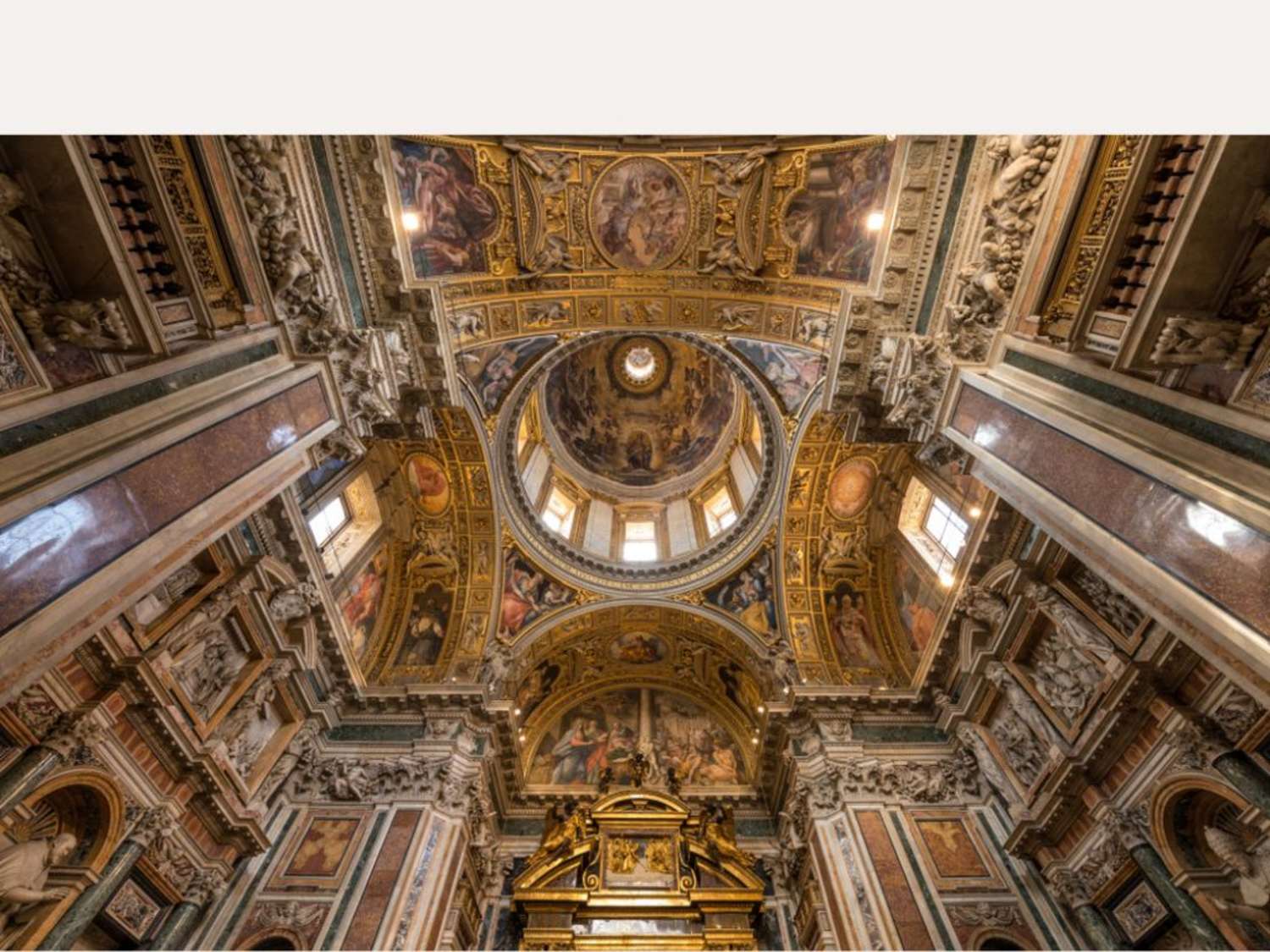

The Pauline Chapel gets its name from the pope that commissioned it, Paul III, but the principal and the saint from which he gets his papal name merge into one. Indeed, the chapel was consecrated in festo conversionis on 25 January 1540, the day of the year that commemorates st.Paul’s conversion. The first action for embellishing it, its first decoration - without prejudice to the mystery still surrounding the stucco decoration by Perin del Vaga, prepared but almost certainly never completed – was precisely Michelangelo’s fresco with the Conversion of Saul, followed by the Crucifixion of St.Peter in the opposite wall: a shocking and unhortodox thematic asymmetry never tried before, and only deeply understood by the future Caravaggio.

Michelangelo tackles historical painting for the first time in the two frescoes in the Pauline Chapel, that is two historical events in the history of the Church that needed to be realistic. History in art means present, because even if the historical facts took place in a distant past, they materialize before our eyes and must perforce be reconsidered according to a contemporary perspective, proof of which can be seen in the spatial position of the paintings on the wall, the fact that they are offered to viewers on a direct horizontal line, stimulating this past-present synchronism. But the two historical facts did not concern only specific events, they are actually the two founding events - after the coming of Christ - of the early church, becoming doctrinal facts, sacred history, and, to a certain extent, due to the presence of the two martyrs, epic events. Michelangelo, with his self-destructive genius, fomented by his Neo-Platonism that pushes him to undertake impossible tasks - the manifesto of this attitude being his verses “as a flame grows more, the more it’s buffeted/ by the wind, every virtue that heaven extols/ shines the more it is assaulted”- decided to tackle a false consecration genre he was essentially unfamiliar with. The grandeur of the epic narrative features, as an intrinsic element of its truth, a certain stupidity, due to the Utopian belief that there is something worth reporting, a belief that is proved wrong by the mythical meaning of epic compositions, the ever-same of the sacrifice and death of the hero; an anachronistic attitude, which, however, must have given Michelangelo the idea of forcing the two stories to serve as mirrors in which to project the reality of his time: his platonizing humanism prevented him from accepting the heteronomy of the liturgical text, boldly improvising on those two stories, as if the hundred and more square metres of frescoes, in their relationship with the sacred texts, were the visualization of a huge musical cadenza. This musical metaphor is necessary if an art that eludes any attempt at narration, touching the deepest “chords” and where the visible challenges the invisible, has to be understood. From this standpoint Michelangelo's work here is an attempt to revoke - through the immanent movement of the concept as unfolding truth - the a priori untruth of historical painting*.* The dramatic situation of the two saints become the artist's aesthetic fight for an autonomous form, where painting becomes the touchstone to test what happens to the charmed aesthetic circle in its collision with Reality.

While the Ceiling and the Final Judgment in the Sistine Chapel can be compared to two symphonies – the Heroic and the Tragic – with their superb annihilation of the detail in the development, the Pauline Chapel, instead, has the effect of a mirrored lieder, with the two soloist voices of Paul and Peter and the orchestra of surrounding secondary figures. Michelangelo’s later style is born here, where the particular - the individual detail - sets itself free from totality for the first time. The particular had always been featured in his art, but at the same time it somehow wasn’t there, it was irrelevant, and one of the meanings of his painting was precisely this unveiling of the nullity of the particular by the whole, the totality. The relationship of the whole with the individual detail, their integration, showed the desire to reconcile the universal and the particular, which only art could pursue, despite the unreconciled reality outside art. Here in the Pauline Chapel the awareness of the non-identity of the whole and it parts becomes stronger, at least as strong as the soundness and predominance of their previous amalgamation, the hitherto balanced strains now openly surfacing. Totality is impeded here, obliging the single figures to close themselves up as if - notwithsatnding the gigantic effort of the two huge paintings - Michelangelo's intention was not directed ar asserting his subjecyive intention but at eliminating it.

Michelangelo’s Pauline Chapel is like a lied for voice and orchestra in two parts. The first and more fantasizing part, with a sense of improvisation and immediacy, is the Conversion of Saul (fig.1); the second is the Crucifixion of Peter (fig.2) firm, objectified around the imposing body of the saint and his cross, but with the character of a decisive act of will, a turning point: it must be so!

The Landscape or of Natural Beauty

Vasari was the first to have focused his attention on what both frescoes have in common: the absence of landscape. He intelligently perceives how the lack of landscape is the result of the extreme spiritualization of Michelangelo’s art at the peak of his artistic life.

The irrationality of nature, its demonic side is embodied by the horse that is launched in flight towards the background of the Conversion (fig.1) barely restrained by a soldier. The neo-platonic theory of furor has been mentioned: furor naturalis melts away and no longer has a reason for being there where the furor divinus takes hold. One can try to be more precise, however, and attempt to liken this horse to Ficino’s “bad horse”. Ficino, in commenting Socrates’dialogue in Plato’s Phaedrus, in a context in which the nobilitating force of love is being discussed, describes the charioteer of the soul pulled by two horses. One is the ‘good horse’ and represents reason, and the other is the ‘bad horse’, standing for “confused fantasy and the appetite of the senses”.

The furor naturalis had been one of the foundations of Leonardo’s poetics. In the compendiary climate of the Pauline Chapel, as the summation of all previous experiences, Michelangelo shows that his art is not afraid of incorporating elements extraneous to it and that it ultimately annihilates. The absence of nature-related details is a sign of the controversy with Leonardo who was the investigator of natural beauty and who brought nature into his art with veiled esoteric rather than knowledgeable values, giving Michelangelo further reason for excluding it.

The landscape in these two scenes is a third and abbreviated dimension, a figured suspended no man’s land, the mute witness to the irruption of the fourth and fifth dimension of that kingdom of the spirit that explodes, uncomprehended by everyone except for Saul, and of which in the Crucifixion of Peter there is only the doubtful expectation in the outbreaking of human horror.

From the point of view of theology the state of nature is separated from the state of grace. Landscape is nature, and Michelangelo’s deep religiousness bans its depiction because it would be the image of divine creation, an intact nature, this side and without society, that is human beings, something that is no longer possible after the fall from grace of the original sin. His transcendental art thus positions itself against nature because the spirit must position itself against it, acknowledging it as diabolical, in the external reality as well as inside itself. If in Michelangelo natural beauty and artistic beauty are divided, this occurs dialectically. The artistic spirit that in his creations anyhow aims at natural legitimacy, brings with the variety of beautiful shapes that very moment of reflection that dissolves natural beauty because it lacks ideal subjectivity and therefore is not alive. But the objectivity of historical life is similar to natural life, however. His mind is overcome by the super-modern intuition of considering all of history as nature: the moment in which nature and history become commensurable is in the prospect of the fall, of ruin. His saturnine gaze has understood history through the eternal ruin that is nature. Ruin is the allegorical figure of history/nature. No memory of transcendence is possible except through the mediation of ruin, and this – albeit in Michelangelo already secularised through philosophical thought – is what approaches him to Luther and to the centrality that for Lutherans has the theme of innate human badness stemming from the original sin. For Michelangelo, therefore, nature is the figure of fate as natural power; a Godless world, represented in these two frescoes by the landscape immersed in that ecliptic light that is its habitual and permanent light.

An enigmatic landscape, heavy with menace, as indicated by the heavy dark clouds of Peter’s story, and under which only a terrible event can occur, such as an outburst by the divinity or the erection of a cross.

The Bodies or of the Somatic

Michelangelo has always loved to call himself a sculptor, and Renaissance sculpture is the art of bodies. Not just from the artistic stand-point, the nature that here in the Pauline Chapel is projected as a background, in the non-prospective distance, is close to the philosophical concept of infiniteness as opposed to bodily finiteness. In Michelangelo’s painting, the body is proof of the irreducibility of the somatic moment of his art, and exhaustlessly shouts the dignity of the corporeal, also stating that the spirit cannot ever be totally separated from the body. In his art the body is Beauty, Desire, Pain, Death and Evil. Here in the Pauline Chapel, the two bodies of Paul and Peter dominate: two dying men, two torments. The corporeal enters the world of morals: Peter’s unbearable physical pain and Paul’s moral pain. The moral of Paul’s scene becomes real in the materialistic motive of Peter’s physical pain, depicted without embellishments. The corporeal is divested of the domain of the spirit and is revealed as absolute evil. Among the living, the somatic and senseless level is the theatre of suffering that unhappily burns whatever the spirit has that is uplifting and with it its objectivation: culture! Corporeal pain destabilises metaphysics. Metaphysics becomes materialistic.

Only art can overcome the apocryphal ambit that threatens all theological/metaphysical speculations, a consequence of the concept of transcendence as the separation of body and soul. Here in the Pauline Chapel the bodies are clearly visible and, although some are transfigured and disfigured by pain, hope remains attached to the bodies. Bodies and their limbs are often mentioned in Paul's theology.

The Pauline Chapel deeply develops the dialectics of the body, it is itself a monument to the body, physical and metaphysical at the same time, like the body of Christ treasured in the consecrated host kept there in the Holy Tabernacle. For Michelangelo the sculpted/painted body has to be preceded by the drawn body. Drawing is central to Michelangelo’s art, it is the generator of life but subtends death in the anatomical study from which it depends. His pencil, his ‘sanguine’, is only the spiritualized version of the scalpel that cuts into the flesh of the cadavers, a sadistic gesture both in anatomy and in drawing because it slits, isolates, rips and delimits, devastating the placid unity of the whole with the highlighting of the contour&detail. Sadism in Michelangelo is the other face of his masochism, the two sides of his desire. No one seems to have noticed that Michelangelo continued to dedicate his time to dissections well beyond his youth and into his senior years. The practice of anatomy speaks of the presence of death, contemplated by Michelangelo in the limbs of the deceased, in the features of the agonising men, as in his own features deformed several times in these years by almost deadly illnesses, or the death felt in losing his brothers, his friends and his loved ones, the death that reverberates upon the classical moral personified in the beauty of the virile bodies. The beauty of the male body, with the desire that turns on, speaks of the vital power of eros, an illusory and fragile bastion – but for this reason all the more precious – against senility and death.

The beautiful and provocative male body is firmly present in these last two frescoes, especially in the first one, the one with Paul, for the obvious reason that the scene envisages the presence of angels, that Michelangelo as usual painted in the nude and especially handsome. It is not untoward to recall here some facts from Michelangelo’s life, however, seeing that the painting of the Conversion of Saul occurred in the years of his liaison with Cecchino Bracci, and the fresco being finished immediately after the death of the latter. To this end, two figures draw our attention. The first is the naked angel who seems to float effortlessly in space in the upper left portion of the painting (fig.1). Its position in the fresco indicates that it was painted in the early 1543. The carefully detailed anatomy, the beauty of the nude with its strong buttocks, are such a hymn to the pleasure of the senses and of the flesh that it seems obvious to connect it with the appearance of Cecchino in Michelangelo’s life. Could that face be a portrait of Cecchino? It is very likely that elements of Cecchino’s face may have taken part in its conception, but they have been rendered more generic than in a real portrait due to the strong influence of the idealising element, so that the perfection of the face recalls certain porcelain complexions of the “ignudi” of the Sistine vault. Instead one of the last figures to be painted just a short while before the fresco was completed in the late 1545 - the youth that seems to rise form the chapel into the lower right part of the scene together with his fellow soldier - has all the flagrancy of a real person, who cannot be other than Cecchino who is now painted with more realistic face and hair colour and is dressed very much as Cecchino would have been when meeting with Michelangelo. The resemblance with Cecchino’s bust on his tomb at the Ara Coeli church is remarkable and the bust was sculpted by Michelangelo's pupils but based on his drawing. The tomb was indeed being prepared right at that time, the end of 1545. What stands out is the carnality of that body, the impetuous muscles of the thighs and buttocks, barely contained by the britches that outline their shape like a second skin, so much so that if it weren’t for their colour he would seem naked. Certainly, there must have been a preparatory drawing made of the boy in that pose, and most certainly in the nude. To this regard, one should ponder the situation of a modern viewer in whose eyes the flagrancy and erotic charge of such a figure is greatly dampened by almost two hundred years of photographic realism. The figure of this boy-soldier, together with the older companion to his right, not simply has a spatial value - cut by the frame he gives greater breadth to the painting indicating the ‘beyond’, the chapel’s real space from which he is ascending. But by identifying him with Cecchino Bracci, his position and movement take on a symbolic importance: the deceased boy leaves the real space of life and ‘ascends’ into the painted space, the ne varietur space of art where death is powerless.

The composition of each of Michelangelo’s frescoes serves as the constitution and exaltation of the bodies, but here in the Pauline Chapel a negativity appears that goes beyond the conscience of the incompleteness of this constitution. It is as if the mortuary stasis of his anatomical studies dialectizes with the “forced” torsions of the bodies depriving them of their energy; the muscles, although still pronounced, become impotent, a heavy load to bear. These torsions are like the sforzati in music: a theory of Michelangelo's body postures will need to be developed. They are dialectical knots, they are the determined negation of the fixed pattern, 'determined' because they yield their meaning only when measured against that pattern. They manifest a radical alienation, foreseeing the edges and fissures of XX century art.

The gigantic size of the bodies, that reaches a peak in the Crucifixion of St. Peter, and the ‘volubility’ of their proportions, registers the shock of the violence extraneous to the ego exerted by the merely existing, and also visualises an extraniated subjectivity with respect to the shapes it is forced to take, and therefore extraniated from itself. It is that upside down world Peter is looking at. The absurdity of the proportions of the figures of the two frescoes seems to have been noticed by every dunce, but what matters is to explain it! It is funny how attempts are made to reduce the strength exuded by the melancholic giant - who acts almost like a telamon for the right-hand side of Peter’s crucifixion (fig.2) – by claiming that his disproportionate size becomes normal when seen from the altar, as if Michelangelo were a painter of anamorphosis!**

The renaissance theory of proportions is erased to exalt the transcendent, the aesthetically inebriated, as the gigantic of the accumulated pain.

The Idiomatic

Idiom is a wide-ranging concept extending from pre-existing language of art to its form. Michelangelo's last two frescoes enjoy the superiority of their mystery that certainly cannot depend from their non-accessibility to the general public and therefore the ensuing negligence on the part of the cultural industry. A useful element for explaining this mystery is to investigate the role played by convention in these works. While the Sistine vault and the Last Judgement itself were deeply unconventional, in the Pauline Chapel the conventional manners are well represented: Christ is traditionally bearded, the down-to-earth gestures of many figures, the presence of ugliness. These conventional formulae would hardly have tolerated before. Convention is often made visible in unconcealed, untransformed bareness, and not so much because of the biographical reasons linked to old age and illness resulting in a kind of indifference for appearance. This indifference is motivated by aesthetic reasons. The new formal law here consists in the relationship between the convention/tradition and the subjectivity that is revealed in the thought of death. Death is imposed on living organisms not on inanimate things, in art it appears in a refracted form: as allegory. Michelangelo’s irascible gesture in life, once transported into art, becomes Peter’s face at the instant of his martyrdom, and has the artistic meaning of attacking the illusionistic semblance of art under the urgency of the thought of death. Touched by the thought of death, Michelangelo’s hands frees those masses of material to which he formerly gave shape, witness to the powerlessness of the Self that confronts the Being. Thus, rough materials and traditional and conventional pieces, no longer penetrated and assimilated by creative subjectivity, gain the upper hand; fragments that have fallen, as if abandoned to their own devices, become the expression not of an elusive weakening of the artist’s Ego but of the mythical nature of the created being and of its fall. Here, the ugly speaks for itself.

But all this is just one aspect of the problem because the subjectivity that is retreating or is under attack picks up all of these rough and conventional elements and once again permeates them with its intentions, in a battle with an uncertain outcome. This explains the increase and decrease in size of the figures, against all likelihood, or the multiplying of the question about the artist’s identity, namely the depiction of his own face in different moments of his existence, like in a sonata or a lied where the fortissimo and the pianissimo, the crescendo and the diminuendo are placed one after the other without intermediate passages and apparently independent from the structure of the composition. The latter is no longer a fully rounded image, the whole is ripped open by the rays of fire of subjectivity that, in its desperate and persistent dynamics, crashes against the walls of the fresco. The artwork continues - as always in Michelangelo - to be a process, but not a development anymore; it remains set between two fires without a medium point of pre-established harmony, clashing inside it the two extremes of the composition as a unitary block and a plurality of eccentric voices. The sudden discontinuities of the various sections or fragments are once again attacked and transformed by subjectivity into moments of stillness and moments of movement. It is difficult to tell if one is viewing a triumph of objectivity or of subjectivity. The fractures and discords in shape are objective, while the light/color that amalgamates everything without harmonic synthesis is objective.

These two profoundly dualistic works fall apart in the present under the disassociative objective/subjective force, waiting for an answer in eternity.

The Ugly

The solid yet larval creatures of all kinds of the Crucifixion of St. Peter appear in pairs and in groups, often marked by infantile features fluctuating between compassion and cruelty, like the savages in children’s books. The thin veil that covers the uncertain and fragile individual identity is lifted to reveal the fear of the ugly. Ugliness is the limited value of the pictorial atom, it is an allegory and incarnation of the extra-artistic reality of suffering. Ugliness is the visualization of the banal. Under the glass case of the transparent surfaces, distorted and colored, the gestures of the human figures, their expressivity deformed along with the objects, the details of the armors and of the clothing, all wakes up to a second and catastrophic meaning: that of the banality of objectual life abandoned to itself. Debased by the lack of divine illumination, men, women, objects and details become the prefiguration of what for us modern is the banal nature of goods as appearance. Immense is the audacity of this attempt to integrate the ugly and the banal in art: the unaware and ugly figures, despite the powerful muscles of the men - that now resemble a straightjacket rather than heroic prowess, as if to underline mankind’s incapability of compensating the weakness of the soul - the pettiness of the female servants and of the soldiers, depicted in their objectual extraneity, and therefore similar to objects, however is never mocked but rather postured in order to express infinite compassion for human narrow-mindedness.

For the first time in a painting by Michelangelo, the viewer so visually close to the drama of the two saints is asked only to be ready to accept what the artist offers, without scaring him, even if he does ask him to follow in his research on mankind, there where its condition is more miserable.

There where man-on-man violence persists, the beautiful and the ugly blur and become equal under the sign of the non-human, of the feral, of the bestial element that expresses itself also through beauty. Indeed, beauty is not absent in the Crucifixion of St. Peter, and as usual with Michelangelo, it is associated with youthful virility. And here we find an absolute iconographic novelty: in the martyrdoms of saints in general, and in that of Peter in particular, ugliness had always been used to indicate the badness and immorality of the torturers, continuously from Lippi to Caravaggio and beyond. Here in the Pauline Chapel, instead, it’s Peter’s Christian followers who are ugly. Tapping the most secret roots of his soul, his deep and unforgiving knowledge of himself, Michelangelo gives shape to the sadomasochistic component of desire by giving the torturers angelic countenances. Here too, though, the nuances are many in the function of age: the handsome face of the commander on the horse, on the left side of the painting, shows an animalesque nervousness that he shares with the sly look of the soldier who is lifting the cross on the right, while the figure with the blue shirt and blue eyes, being the youngest, has a face that is not only handsome but also innocent, with that white band holding back that blond hair, at the same time symbol of victory and the Dionysian headband, yet remaining the best way for workmen to keep the sweat out of their eyes.

Beauty now is no longer the Neoplatonic stairway to heaven. The beauty of these faces is like the flower blossoming from a monstrous plant: pure appearance, false existence that produces the fruit of evil as its truth. Neither the beautiful nor the ugly provides any guarantee. In the falsity of life lived under the constriction of evil, all that is left for living beings is a false alternative, namely that of a forced ataraxia or the abjection of those involved. Even the conceptual opposition of young/old that descends from the beautiful/ugly proves to be a false alternative.

The confusion between beautiful and ugly is therefore the paradox of the entire paradoxical scene of Peter’s martyrdom, where he himself is not only the innocent victim if his corpulent nudity has something contemptible about it that evokes the long history of doubts and denials of the living Christ, and the oppressors are not only oppressors “for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34).

Paul is as old as Peter. Peter’s old age is highlighted by the exhibition of his naked body, the body of an old man without beauty that Michelangelo had already anticipated in the realistically unattractive nude of the Dusk for the Medici tombs. Paul’s old age is concentrated instead in his face but stands out because of the great detail and because he is the only elderly being in the whole scene around him. In fact, his soldiers are all attractive and young, although declined from adolescence to adulthood to maturity. Old age, however, has a different meaning for the two saints. For Paul, it’s the sign of the infamy of his past - this author has finally found the sources for this unorthodox detail: Augustine's Confessions where it is stated « [...]bringing old age to the proud » - while for Peter it represents the borderline-experience, as he is about to see the world from upside down and is being seen naked by everyone. The experience of being observed in such a circumstance, however, although it is totally loathsome, incomprehensible, and inevitable, triggers the image of destiny. Peter is History, if it is true that only through the image of old age that children first acquire the idea of what history is. Peter’s naked body, although no longer young, still has a majestic beauty that is all the more touching due to the incredible and absurd circus-like situation he finds himself in and that he has contributed to creating with his request, thereby increasing the sense of overall dehumanization: the subject recedes, almost biologically, and the next step will be that of waking up in the form of a giant bug.