Prague is a city of cobbled streets, towering spires, and rich, complex history. But beneath the surface of tourist attractions and charming cafes lies a darker past, a time when heresy, alchemy, and demonic forces were woven into the fabric of the city.

Join Charles, a Context expert based in Prague, on a journey through the city's lesser-known history, meeting the figures and movements that cemented its reputation as a hotbed for the unorthodox. Prepare to be surprised, intrigued, and maybe even a little spooked!

Jan Hus and Heresy in Bohemia

Monty Python lied to you about King Arthur and witches! Inquisitions, formal witch trials, and the burning of heretics at the stake were products of the end of the Middle Ages and postdate the supposed era of Arthur by six centuries. The truth is, the medieval Church was less concerned with heresy and more concerned with... well, your manners.

For most of the medieval period, the Catholic Church in Europe was far more concerned with orthopraxy–correct behavior–than with orthodoxy–correct belief. But around the thirteenth century, increasingly literate lay people began to interpret scripture themselves. It was not long before it began to affect the young Kingdom of Bohemia.

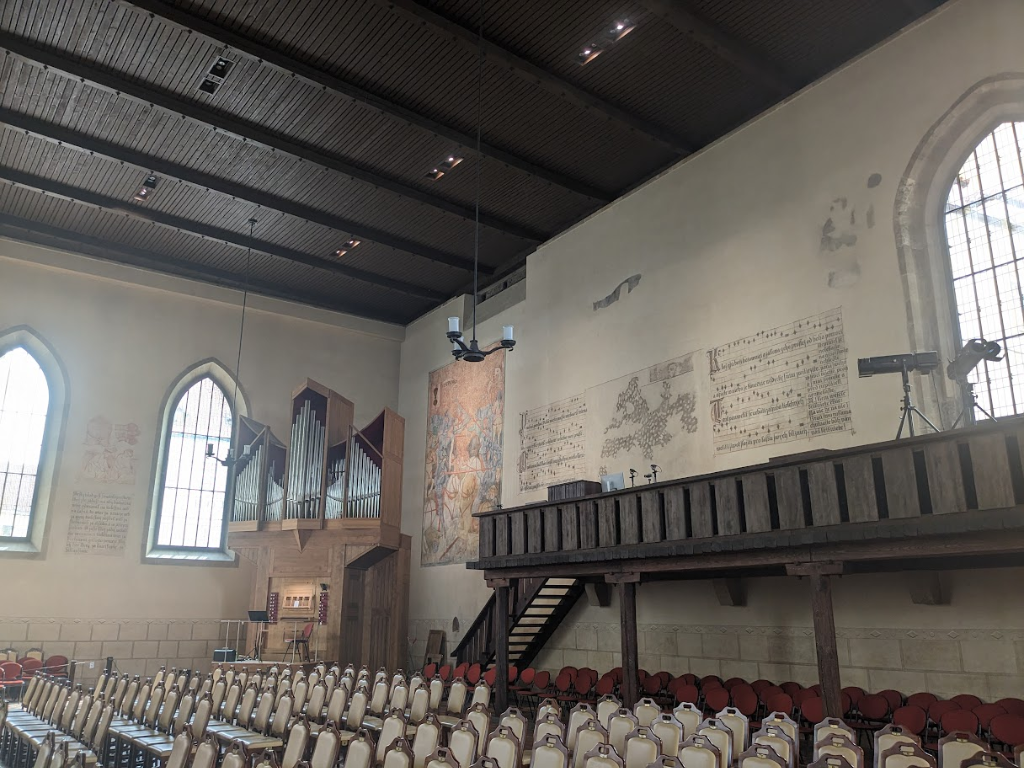

Bethlehem Chapel where Jan Hus preached. Rebuilt from ruins in the 20th century.

Bethlehem Chapel where Jan Hus preached. Rebuilt from ruins in the 20th century.

Arguably the key figure of Czech history, Jan Hus was born in Husinec, probably in 1372. He was educated at the recently-founded Charles University and then taught there, rising to the rank of Dean of the philosophical faculty and university rector. At the same time, he was ordained and began preaching from the pulpit of Prague’s Bethlehem Chapel, which can still be visited today.

Hus denounced the moral failures of senior clergy (including the Roman Pope) and the sale of indulgences, which were sold by the Church in order to raise funds for construction projects and crusades.

These preachings alone, somewhat surprisingly, were not enough to land Hus in immediate trouble.

Soon after, there were two different men who claimed to be Pope, one in Avignon and one in Rome. Charles University found itself pressured to pick a side. Hus was the de facto leader of the Bohemian nation, and at his urging and that of the king, Wenceslas IV, the Bohemians voted for neutrality. The three other nations–Bavarian, Polish, and Saxon–voted to support the Roman Pope.

The Karolinum (the old arts faculty building) at Charles University where Hus was educated and then worked.

The Karolinum (the old arts faculty building) at Charles University where Hus was educated and then worked.

In response, King Wenceslas promulgated the Decree of Kutná Hora, named for the beautiful royal city, which is well worth visiting. This radically altered the voting system of the university, combining the three non-Bohemian nations together and giving them a single vote to share, whilst awarding two extra votes to the Bohemians.

Mired in both academic-political and religious controversy, Hus’ fate was sealed. At the council of Konstanz in 1414-1415, he was arrested, imprisoned, and put on trial for heresy. There, he was presented with a number of passages from his own published works which the council found objectionable. Hus declined to recant any of them saying that he would only do so if convinced they were against the scriptures.

He was then sentenced to death by burning alive.

Hus had been both a popular preacher and, through his academic-political notoriety, an icon of Bohemian nationalism. His execution inflamed Bohemia.

Efforts to suppress the protests failed, and war broke out between the Hussites and the Catholics. The Hussite forces, well-motivated and led by the great Czech hero Jan Žižka won a shocking series of battles against much larger Catholic armies, garnering a fearsome reputation. There are accounts of Catholic armies retreating at the mere sound of the Hussite war hymn, “Ye Who Are Warriors of God.” Today, you can see his enormous equestrian monument that watches over Prague from Vitkov hill, a site of one of his famous victories.

Vitkov Monument to Jan Zizka. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Vitkov Monument to Jan Zizka. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Hussite Wars eventually concluded with an uneasy peace. The Hussites acknowledged the primacy of the Roman Pope, and in exchange were permitted to practice their own liturgy in Bohemia. Hus’ legacy, though, endured. Bohemia came to be regarded as a dangerous hotbed of both nationalist sentiment and religious unorthodoxy.

Rudolf II and the City of Alchemists

Part of Prague’s reputation as a city of unorthodoxy arose, paradoxically, because of a Catholic, Austrian, and Habsburg Emperor, Rudolf II (1552-1612). Rudolf is an interesting figure. Generally viewed as a weak and ineffectual ruler in Austria itself, he has had an enduring impact on the city of Prague and on Czech culture more broadly.

Rudolf moved the Imperial Court from Vienna, which was felt to be in danger from the powerful Ottoman empire, to the relative safety of Prague, bringing with it economic prosperity and an architectural renaissance. But another part of his legacy arose out of his religious, scientific, and occult interests.

Queen Anne’s Summer Palace at Prague Castle, used as an observatory by Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Queen Anne’s Summer Palace at Prague Castle, used as an observatory by Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

From our present vantage, Rudolf’s patronage looks rather eclectic. At the same time that he was inviting the great astronomers Johannes Kepler and Tycho Brahe to court, allowing them to use the Belvedere summer palace as an observatory, he was also inviting the notorious alchemist John Dee and soliciting a royal horoscope from Nostradamus.

In reality, though, many of the intellectual distinctions that we now draw were as yet unformed in the 16th century. Then, philosophy blurred into theology; astrology into astronomy; alchemy into chemistry. It was not at all unusual for men of science to also be magicians and alchemists: Brahe was himself an alchemist, as was Isaac Newton. By the standards of his day, Rudolf’s interests were broad but perfectly consistent.

Rudolf’s patronage was surprisingly non-denominational. Kepler and Brahe were both Protestants, Dee a distinctly heterodox Christian mystic. More surprising still, Rudolf extended an official policy of toleration towards Jews.

Under his reign, Prague’s Jewish community expanded to become the largest in the world and its Jewish quarter grew large and wealthy. Medieval Jewish mystical tradition was becoming more widely known among Renaissance Christians. We know from court records that Rudolf met privately with Prague’s chief Rabbi, the famous Judah Loew ben Bezalel who had a reputation as a scholar of Jewish mysticism.

The Old-New Synagogue. Rabbi Loew was Chief Rabbi here in the time of Rudolf II. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Old-New Synagogue. Rabbi Loew was Chief Rabbi here in the time of Rudolf II. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Speculum Alchemiae underground alchemical laboratories.

Rudolf’s legacy extends to some sites outside the Castle and Jewish quarter. My favorite of these is the so-called “Faust House” on Charles Square. The current house dates to 1769, but the former residence had a reputation as a haunt of sorcerers and magicians. In Rudolf’s day, it was the home of Sir Edward Kelley, an English occultist and colleague of John Dee. Subsequently, it was owned by a series of eccentrics, including the chemist Ferdinand Antonin Mladota, whose experiments reportedly caused periodic explosions and punched holes in the ceiling.

Today, hardly anyone is an alchemist. The alchemical sites of Rudolfine Prague remain, however, a testament to a time when science and magic had yet to go their separate ways.

Demons and Devils

Medieval people generally believed that the demonic was a real, literal force. Demons were thought to be active in the world, using supernatural powers, causing plagues, leading humans to sin, and other such villainy. It is not surprising that medieval art sometimes includes demons. This was true everywhere in Europe, but Prague, with its complex religious history and large community of artists and craftspeople, was a particularly fertile source of demonic art.

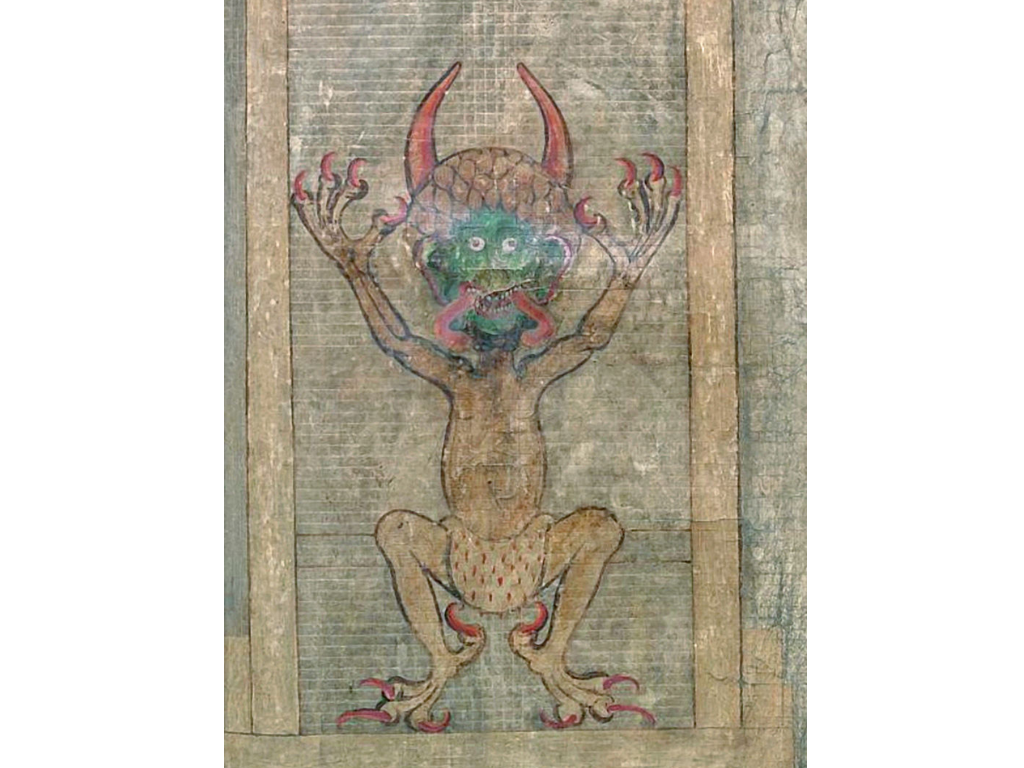

My very favorite piece of Czech demonic art is the Codex Gigas, also called the “Devil’s Bible." It is the largest illuminated manuscript in the world. It was produced in the Kingdom of Bohemia sometime around the year 1200 and resided in Rudolf II’s private library before being looted by the Swedish army during the Thirty Years’ War. The original is now in the National Library of Sweden, but a wonderful full-sized digital version is in the National Museum in Prague.

The Devil, Codex Gigas folio 290r (ca. 1220). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

It also includes a wonderful full-page illustration of the devil, with large red horns, a forked tongue, and prominent claws.

This illustration was extraordinary even in medieval times. The pages of the Codex Gigas surrounding the devil are unusually yellowed and light-damaged from centuries of readers leafing through exactly these pages to find the devil illustration!

Other infernal artworks can still be found in Prague. I was recently visiting the medieval art collection in Prague’s St. Agnes Convent where I came across a fourteenth century altar painting of Saint Margaret of Antioch.

Saint Margaret carrying a demon, one third of an altarpiece by an unknown master.

Saint Margaret’s legend involves her battle with and escape from the devil in the form of a dragon, so art tends to identify her by showing her fighting, trampling, or otherwise struggling with a demonic dragon. Eastern Christian artists generally focus on the battle, and western Christians focus on the moment of triumph. The unknown Czech artist of this altar, though, has opted for a much more ambiguous image, where the saint is simply holding a rather jolly serpentine demon. I am not entirely sure what to make of this piece, but it is certainly intriguing.

Architects and sculptors, as well as painters, sometimes turned to the demonic for inspiration. Many medieval buildings feature grotesques–monstrous, but often humorous, architectural elements designed both as decoration and as a kind of supernatural protection. In Saint Barbara’s Church in Kutná Hora, the builders included several peculiar cat-demon grotesques. This type of axe-wielding feline is, to my knowledge, unique to the Czech lands.

An axe-wielding feline demon, from the lapidary exhibit at Saint Barbara’s, Kutna Hora.

Another remarkable bit of demonic art is to be found in the floor tiles of the partially-excavated medieval Basilica of St. Vavřinec in the fortress of Vyšehrad. Here, an artist has included, amongst demonic beasts, griffons, and sphinxes, tiles showing the Roman Emperor Nero imagined as the Antichrist. The symbolism is much more overt: churchgoers walking up to the altar would literally trample the demons and the Antichrist underfoot.

Prague: A City of Mystery and Magic

Prague's unique history continues to shape its character today. Tourists flock to see the astronomical clock and the remnants of the Jewish Quarter, unknowingly treading the same ground as revolutionaries, stargazers, and those who dared to dabble in the forbidden arts.

Remember that Prague is a city that rewards the curious. Look beyond the postcard beauty and you'll find a place where heretics, alchemists, and demons lurk, waiting for a discerning eye to reveal their stories.

About Charles:

Charles is a historian and philosopher who studies medieval and early modern knowledge production - especially early universities. He also does academic work on the history of demons in philosophical thought. A dedicated traveler, he moved to Prague after having lived in Canada, Germany, the US, and Austria.