Frida Kahlo once described two major accidents defining her life: a bus crash that left her shattered and bedridden for a year...and marrying Diego Rivera.

The love story of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera is fraught with drama of both the public and private variety. Two of the most prominent artists of the 20th century, they held revolutionary emotions and ideas, united in an explosive, passionate, and often detrimental relationship that would last until Frida Kahlo died in 1954. This was a relationship that mirrored the turbulence going on around them — a cycle of infidelity and violent demeanors set against the backdrop of a country reshaping its identity, a World War, and political upheaval.

Both were passionate about the rebirth of their country’s identity soon after the Mexican Revolution; the artists first met in 1928 through the Mexican Communist Party. Rivera was twenty years older than her and had already amassed fame for his incredible artistic talent. A child prodigy, painting had always come naturally to Diego. He was given a scholarship from the Mexican government to study art in different cities worldwide, including Paris, where he befriended Cubists like Picasso and other influential artists. Kahlo was almost instantly enamored with this man whose ideals about Mexican identity closely matched her own and who encouraged her artistic flourishing.

Frida and Diego married one year later, in 1929, perhaps with a slight intuition about what would come.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera: Their Art and Affairs

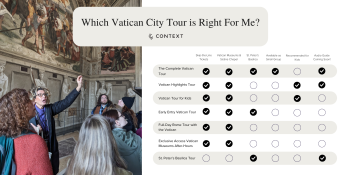

Upon meeting Frida, Diego Rivera was still married, divorced once, had a mistress, and produced children with almost all of these former women. This wouldn’t be the last time that Rivera would be unfaithful, and Kahlo also had her fair share of lovers. Rivera’s extramarital affairs include Kahlo’s sister, Cristina, an experience Kahlo processed with a violent portrayal in A Few Small Nips (1935). Leon Trotsky and Georgia O’Keefe were among the famous lovers that Frida took. Over the course of their relationship, Frida and Diego would often illustrate the other in ways that were true to their hot and cold dynamic, at once adoring and spiteful.

A Few Small Nips (1935) by Frida Kahlo - Image Credit - Lluís Ribes Mateu | Flickr

Still, Diego Rivera left all of his Parisian exploits behind, found Frida Kahlo, and both of them began to contribute to the post-revolution reinvention of Mexico. Between 1930 and 1934, the married couple traveled to the United States where Diego was commissioned to paint a mural at the Pacific Stock Exchange Luncheon Club and the San Francisco Art Institute. Active members of the Communist Party, Frida, and Diego both abhorred the American capitalist way and often depicted Communist motifs in their artwork. They made a good artistic team in that way, each encouraging the other in their strong ideals and beliefs.

Kahlo suffered a series of miscarriages during this time, which she depicts in her piece Henry Ford Hospital in 1932, another painting that makes sense of her life experiences. Of the many symbols hovering above and below the bed is a decaying purple flower, which likely represents Diego who Kahlo never thought would make a good father.

Henry Ford Hospital by Frida Kahlo - Image Credit - FridaKahlo.org

The miscarriages were just one event in Frida’s long struggle with her body’s endurance. When she was six years old, a battle with polio left a permanent limp in her right leg, a leg she will have to amputate in the final chapter of her life due to gangrene. Aside from her bus accident, she also had to undergo a series of operations in the ‘40s trying to fix her back, which left her with more pain. But these body plagues never deterred her.

The Dualities of Frida Kahlo

At her very core, Frida Kahlo was a fighter. The image of resistance, of challenging social norms, and of the independent woman ties her portraits and paintings together. Her themes of duality are born out of resistance: Mexican versus European, Christianity versus Aztec beliefs, and masculinity versus femininity. Her relationship with Diego Rivera perfectly encapsulates Kahlo’s duality within herself, an internal conflict that was kindled by the problems of the world around her. We can see this most presently in her painting Frida and Diego Rivera (1931). She portrays Diego as she saw him in their beginnings, an artistic giant compared to her smaller, more elegant frame. He preferred that she wear traditional feminine Mexican clothing instead of European fashion to show her allegiance to the people, and liked her hair long in spite of Kahlo feeling more masculine. In later paintings, she’ll resist these ideas, depicting herself with shorter hair, donning a suit, or having facial hair, in part to challenge Rivera’s toxic masculinity. Her inclination for resistance also acted as a duality for Rivera as well — something that attracted him, but also caused tension for them.

Frida and Diego Rivera - Image Credit - FridaKahlo.org

The painting foreshadows certain aspects of their relationship. In spite of Diego Rivera’s sturdy figure, their grasp is loose, indicating that Kahlo won’t be able to rely on him as a partner. His sturdiness is just an illusion. This grasp contrasts from Frida’s grasp in The Two Fridas (1939), where her hold is much firmer, realizing that she has only herself to depend on.

The Two Fridas - Image Credit - FridaKahlo.org

Diego's Legacy and Immortalizing Frida Kahlo

Yet, Kahlo and Rivera continued with their chaotic relationship through a divorce and another remarriage. A story as old as time, they knew that they weren’t good for each other, but they stayed together nonetheless. Diego was there in the final years of Frida’s life. Ten days before her death, they attended a march together, always united in their fervor for social change. Frida handed Rivera a ring that he bought her for their 25th anniversary in one of her final acts before dying. Soon after, Rivera turned her famous house, La Casa Azul, into a museum. As volatile as their marriage was, preserving Frida Kahlo’s legacy speaks volumes about the tenderness that Diego had for Frida.

The love story of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera could be a work of art in and of itself. Complicated, full of contrast, and a product of its time.

Inspired to dive deeper? Visit La Casa Azul with us in person!