A City in Tune: Exploring Vienna’s Storied Opera Heritage

The Vienna State Opera Building

By Giacomo Mura

During the regular opera season that begins in the middle of September and runs through June, one can find several performances of a variety of operas in the main theaters of Vienna.

During my years-long attendance of the many opera houses of Vienna, I have never witnessed a half-empty hall, despite the large frequency of the representations. There is no greater testament to the enthusiastic involvement of the Viennese people in the wonderful tradition of Viennese music and opera.

Viennese Opera's Origins

The undying love Vienna has for opera is ancient. It was in the 1620s, exactly four centuries ago, that Vienna was first conquered by this new, irresistible genre. Opera was a cultural product of Italy, being born in Florence around the beginning of that century, and was on a triumphal march of surging popularity across Europe.

Vienna had a lasting love affair with Italian music in general until the middle of the 18th century, with strong implications even up to the beginning of the 19th. It is very telling that between 1619 and 1741, out of the eight court composers that directly served the imperial family, six were Italian.

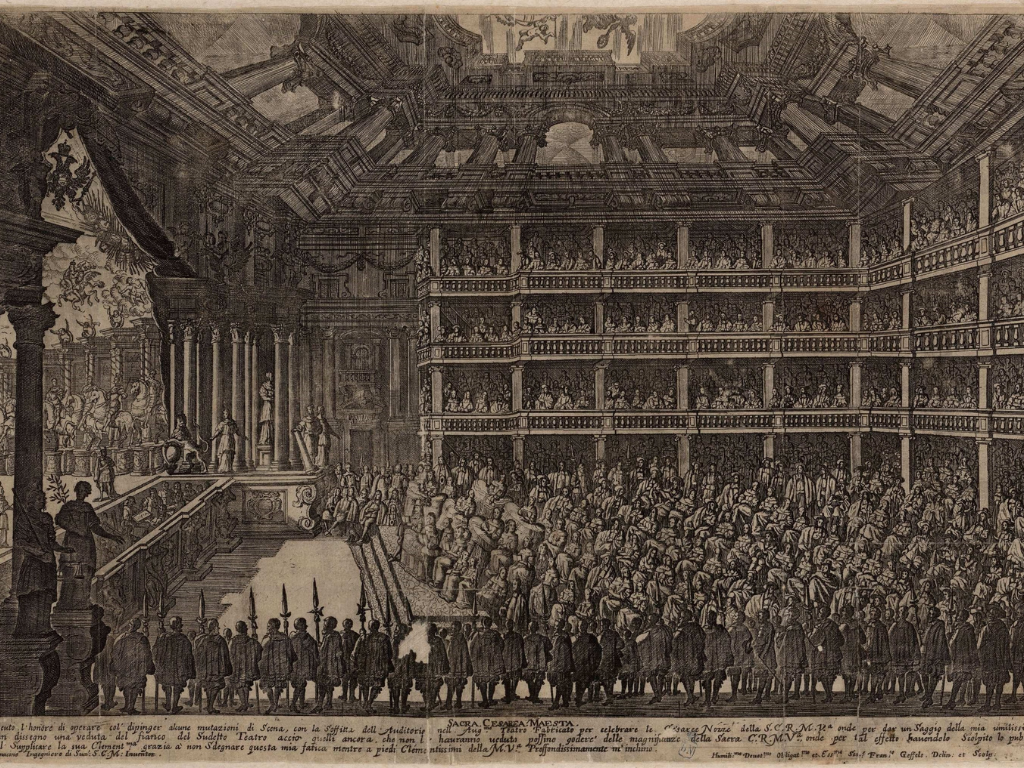

With such a love for music, there was a strong need for an opera theater in Vienna. The task of building the first theater for the court was, of course, given to an Italian architect, Ludovico Ottavio Burnacini, who completed it in 1668.

A print of Burnacini's theater

A print of Burnacini's theater

Curious to hear what all the fuss was about? Listen to an example of the late Italian baroque opera with this piece from an opera by Antonio Vivaldi, a personal favorite of Emperor Charles VI:

The agility of this singing is astonishing, isn’t it? This perfectly summarizes the baroque Italian operatic style; the greatest attention was given to the spectacular vocal pyrotechnics of star singers, as well as jaw-dropping sceneries and visual theatrical effects. However, the quality of the music itself and the dramatic power of the opera were not as important as one might think… until a big turn of events occurred.

Gluck’s reform

In the 18th century, a cultural earthquake shook the tranquil Italian-flavored opera tradition of Vienna when Cristoph Willibald Gluck produced and presented a new model of opera.

While Gluck's reform is usually explained through an artistic perspective, that is not the entire story.

It is true that one of Gluck’s goals was to remove some of the spectacular traits of the Italian opera, bringing compositions back to a purely artistic purpose. But in reality, the actual reason behind his reform was part of a political strategy, planned by the government of the Empress Mary Therese.

Statue of Cristoph Willibald Gluck

Statue of Cristoph Willibald Gluck

This story is truly fascinating and shows how cleverly music and art have been used by those in power.

The political mind behind Gluck’s reform was Prince Kaunitz, the prime minister of the empress who de facto decided the policies of the empire.

Until that point, Europe was the fighting ground of the two leading ruling dynasties: the Bourbons of France and the Habsburgs of Austria. They were sworn enemies and even though the many wars fought in Europe saw diverse alliances each time, these two were always on opposite sides.

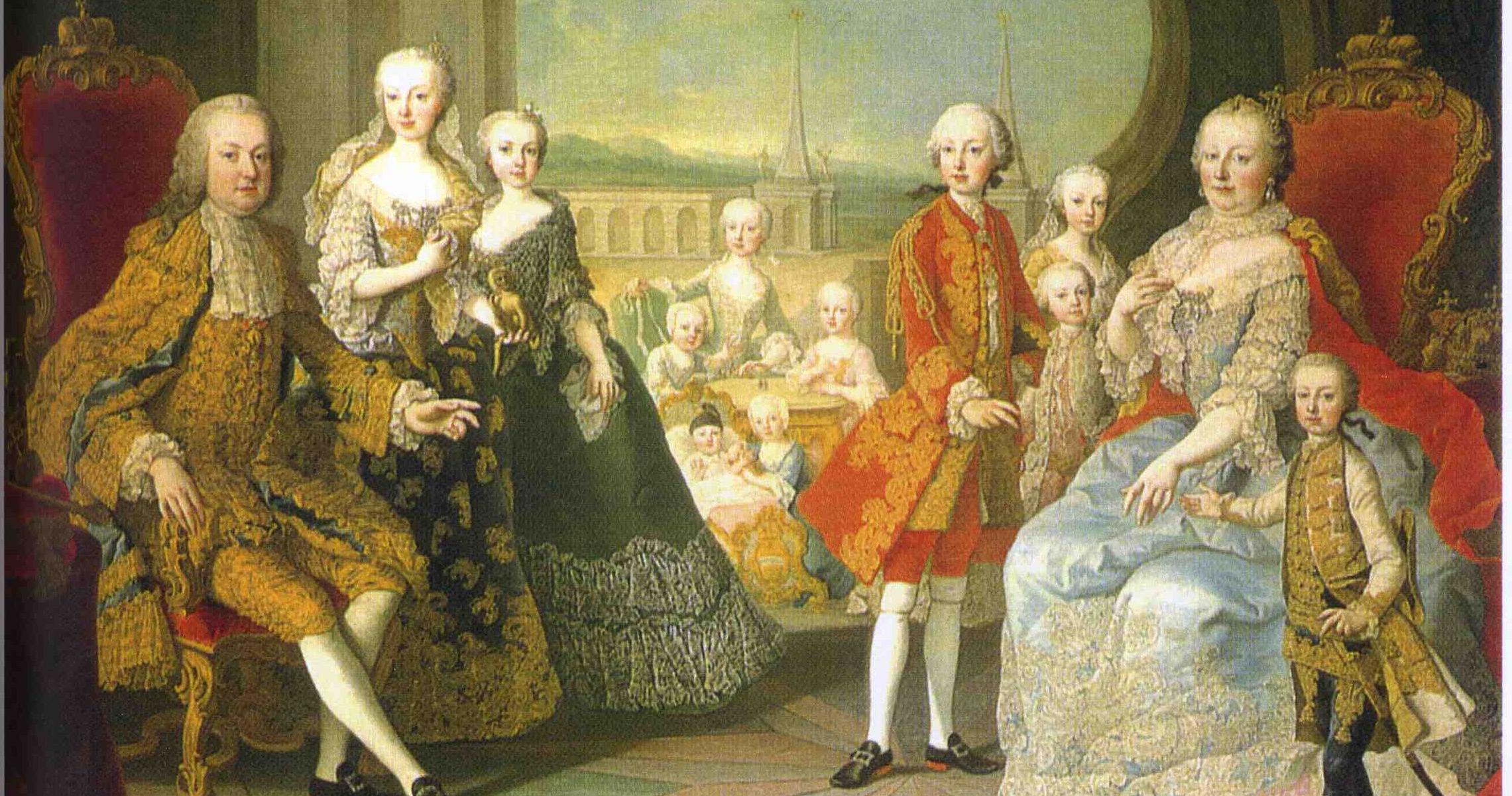

Mary Therese and her family

Mary Therese and her family

However, the war that saw the confirmation of Mary Therese as Empress of Austria (fought between 1740 and 1748) showed the rise of a frightening new military power–the kingdom of Prussia (now, northern Germany) managed to seize the wealthy region of Silesia from the Empire.

Kaunitz was worried. He thought it necessary to make a new alliance against the kingdom of Prussia, and the only potential partner powerful enough was France, the age-old enemy.

Talking of friendship after centuries of wars would not be an easy task.

The first negotiation attempts failed, and it was then that Kaunitz had a stroke of genius; he would use culture to bring the two parties closer. Opera was by far the most beloved genre both in Vienna and Paris, but the latter was the bastion of the only real alternative to the Italian model, the French opera, also known as “tragedie lyrique.“

Therefore, Kaunitz gave the task of fusing French and Italian opera, with the goal that it could be liked by both Viennese and Parisan, to a composer who was then pretty much unknown: Cristoph Willibald Gluck.

Prince Kaunitz

Prince Kaunitz

The opera “Orfeo ed Euridice“ by Gluck was staged in 1762 in Vienna, with astounding success. It is an Italian opera, with the signature melodic and lyrical singing, alongside the dramatic force of the French model, as well as the ballets and choruses typical of the tradition of Versailles.

Listen to the music from the scene when Orpheus meets the Furies in the Underworld. It’s a wonderful showcase of Gluck’s conception of hybrid opera:

In the following years, Gluck went to Paris and had a great career there as well. Kaunitz’s plan was a success.

Comic Opera and Mozart

In parallel with Gluck’s career, a new genre of opera was officially born and rising to fame at a very quick pace: the comic opera, once again coming from Italy.

Unlike the conventional tragic opera, always of mythological or historical subject matter, the comic opera presented realistic plots and characters that mirrored social dynamics and conflicts. It was lively, fresh, full of biting humor and irony.

A stage photo of a comic opera

A stage photo of a comic opera

In order to empower this vitality, the music of the comic opera was daring and innovative. Through the entire 18th century composers experimented with new ways of making the music more dynamic and incisive, including ensembles of singers where the traditional opera would have only featured single-singer pieces. In comic operas, the orchestra played a bigger role instead of serving as a simple accompaniment, as it had in the past.

The absolute peak of this evolution arrived in the 1780s, the golden age of Viennese classical music under the rule of emperor Joseph II, and the decade of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s stay in Vienna.

Within Mozart’s formidable excellence in every musical field, his comic operas shine with the brightest of light: despite being an eclectic, deep down he is primarily a man of the theater with the sharpest dramatic sense.

Statue of Mozart

Statue of Mozart

The three operas he wrote in cooperation with the poet Lorenzo da Ponte are the greatest masterpieces of his period and of all time. All the features of the music developed for comedy are found there in the most perfect execution. Have a listen:

Ensemble pieces where the voices of several characters are combined up to trampling climaxes:

Single arias of huge melodic intensity that reveal the psychology and feelings of a character:

Duets of wonderful musical and theatrical confrontation of characters:

Satirical music where social innuendos make it spicy and biting, like in this example:

In this last piece, Figaro, a servant, sings to his master, challenging him in a menuet. The menuet was the prominent aristocratic dance of the day and servants were not allowed to dance it! To the audience of its time, this made a comparable effect for us to see a waiter waving a golf club at a billionaire inside an exclusive circle.

The genius of Mozart’s comic operas can be summarized this way: the music is so beautiful and brilliant that it can amaze and entertain like no other, even on its own. But together with theatrical action, sung by those characters and within that frame, it empowers the fictional world to an irresistible degree.

The Imperial Theaters

During the course of the 18th century, the demand of the Viennese upper classes for opera materialized in the construction of two great theaters, managed directly by the imperial family.

The most important is the Burgtheater, built in 1741. It was next to the Hofburg, the imperial palace.

A print of the old Burgtheater

A print of the old Burgtheater

This theater was lucky enough to see the premiere of some of the most important operas by Salieri and Mozart, like “The marriage of Figaro“ in 1786.

Later on in 1888 the Burgtheater was moved to another seat, built by the famous architect Semper, which is still active today and can be visited, even though opera is no longer staged there.

The new Burgtheater

The new Burgtheater

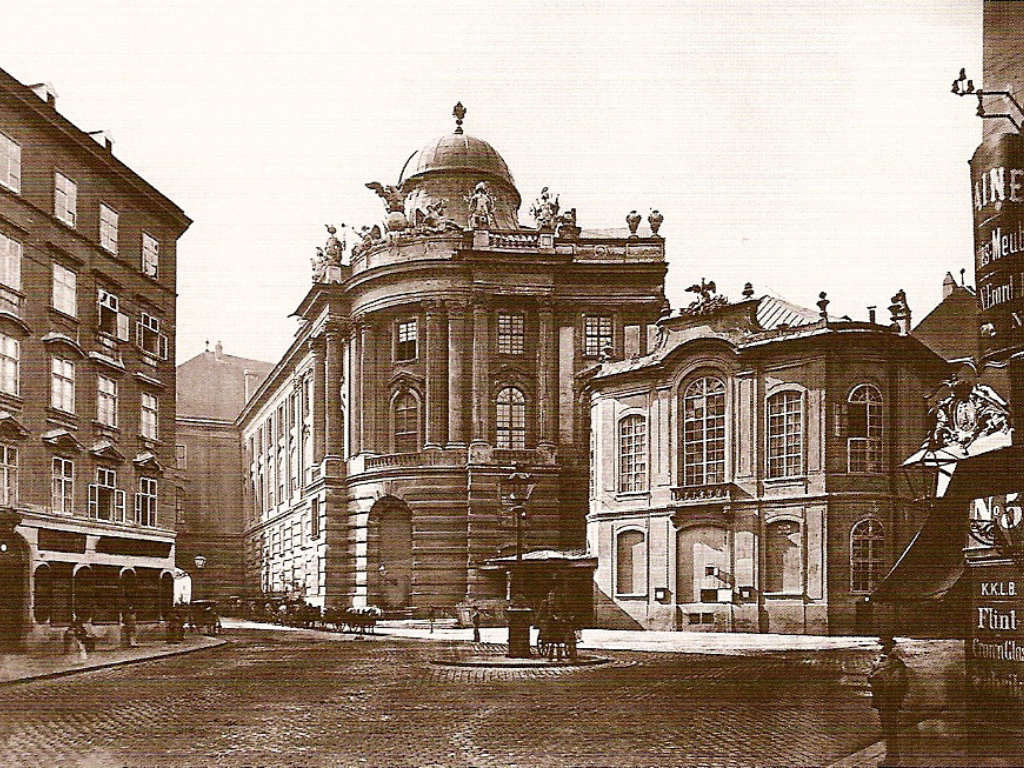

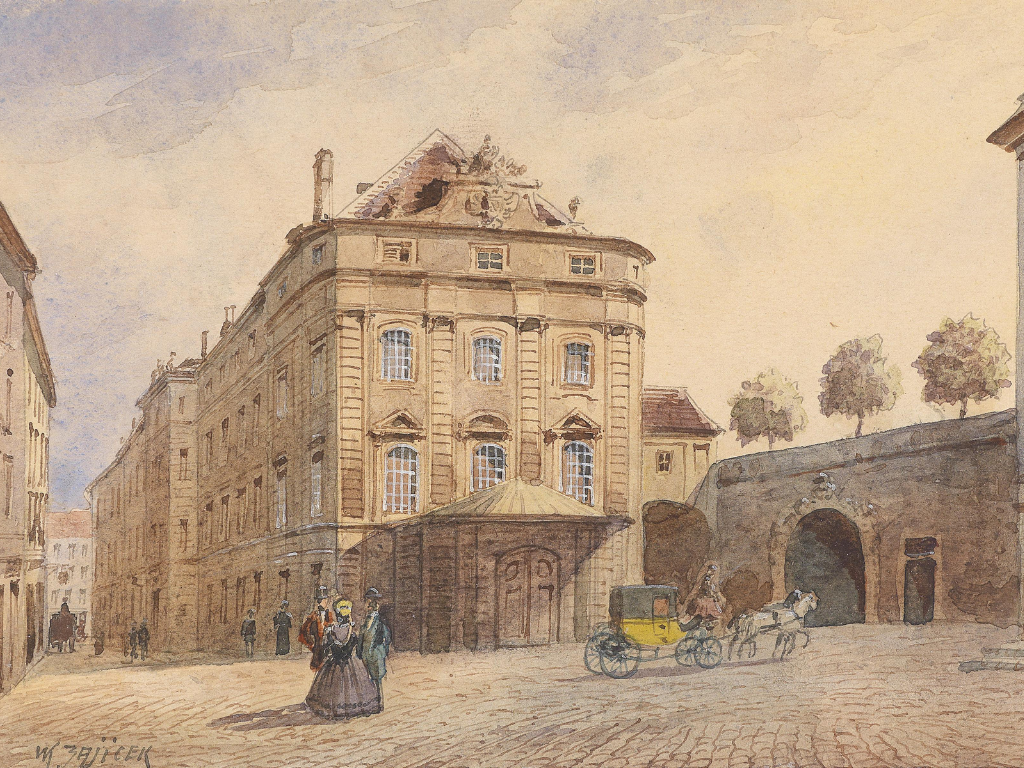

The other imperial theater was the Kärtnertortheater, built in 1709.

A print of the theater before demolition

A print of the theater before demolition

It is particularly connected with the name of Ludwig van Beethoven, being the place where his opera Fidelio and the sublime 9th symphony were first performed.

In 1861 the Kärtnertortheater was demolished, due to the construction of the modern State Opera building right next to it. It was replaced by something of great interest though: the famous Hotel Sacher, the family of the inventor of the world-wide renowned cake.

Hotel Sacher

Hotel Sacher

Exploring Opera in Vienna

As we journey through the centuries of Viennese opera, from the first theater built by Burnacini to the revolutionary works of Gluck, Mozart, and beyond, it becomes clear that Vienna’s dedication to this art form is deeply woven into the fabric of the city's history and culture.

Whether you’re a lifelong opera lover or someone just discovering its wonders, Vienna’s opera scene is an invitation to step back in time and experience music that has shaped not only the city but the entire world.

The grandeur of its past lives on in each performance, offering a timeless connection to the sounds that have captivated audiences for centuries. So, the next time you find yourself in Vienna, be sure to take part in this enduring tradition and witness the magic for yourself.

About Giacomo:

Giacomo Mura is an Italian Classical Music Appreciation teacher. After graduating from Conservatory in Como, he studied under one of Italy's most important music historians, Alberto Batisti. He has been teaching classical music history and theory for over five years, teaching students to listen with greater awareness and enjoyment. For the past few years, Giacomo has held events with the Italian Embassy in Vienna, the Italian Culture Institute, and the Società Dante Alighieri. He also lectures in partnership with "International Study Programs," "The Austral Group," "The Global Exec," the University of Colorado, and "54Traveler."

Even More from Context

We're Context Travel 👋 a tour operator since 2003 and certified Bcorp. We provide authentic and unscripted private walking tours and audio guides with local experts in 60+ cities worldwide.

Search by CityKeep Exploring