What Are the 7 Wonders of the Ancient World?

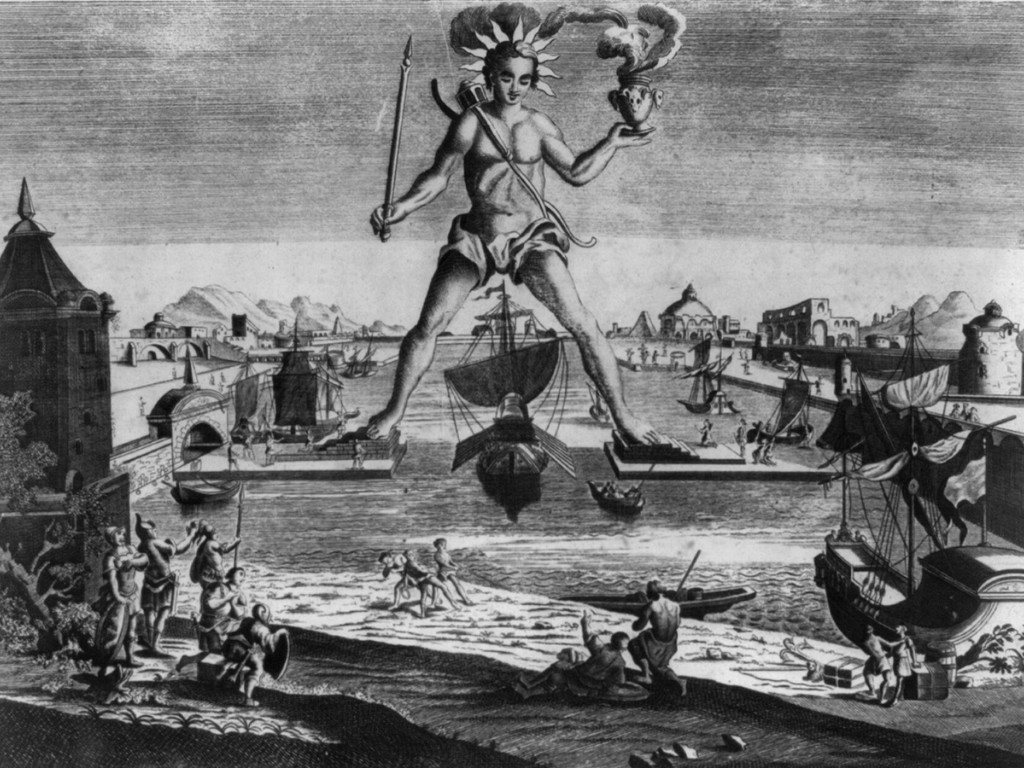

An imagined depiction of Colossus of Rhodes

Every day we learn something new about the ancient world. Who were these people of the past? What did they care about, their hopes and dreams? Fortunately (and unfortunately) a lot of what we know about these mysterious civilizations rely on written texts that have been decoded by archaeologists over time. But what of those societies that didn’t have a written language? What’s more, many civilizations of bygone eras recorded their legacy through the eyes of a powerful elite, so our vision of them is inevitably colored.

Whatever the case, our modern world is endlessly fascinated by who our predecessors were and what their lives were like. The ancient Greek writer, Philo of Byzantium, had the foresight to note the seven greatest ancient marvels of his time for future generations to be inspired by. Of these original seven wonders, only one still remains. It’s also possible that some of them may have not existed at all. The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, not so different from the modern world’s version, show us humankind at her most capable and also most cruel.

1. Great Pyramid of Giza

Giza, Egypt

Have you guessed which one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World survived into the present day? If you predicted the Great Pyramid of Giza, you’d be right. The Great Pyramid is part of a group of three pyramids, each dedicated to a different king for which the tombs were built — Khufu, Khafra, and Menkaura. The Great Pyramid refers to the grandest of them all, designated for Khufu. Covering 13 acres and using approximately 2 million stone squares, it is absolutely mind boggling that early Egyptians pulled this monument together without the help of modern technology between 2700 B.C. and 2500 B.C. Even more jaw-dropping, Khufu’s mausoleum hailed as the tallest building in the world for 4,000 years. It took modern equipment in the 19th century to surpass the Great Pyramid’s height of 451 feet, which could have been even taller if it wasn’t for grave robbers. All three pyramids at Giza were subject to looting inside and out. Stone blocks, burial chambers, grave goods, and more were stolen over time.

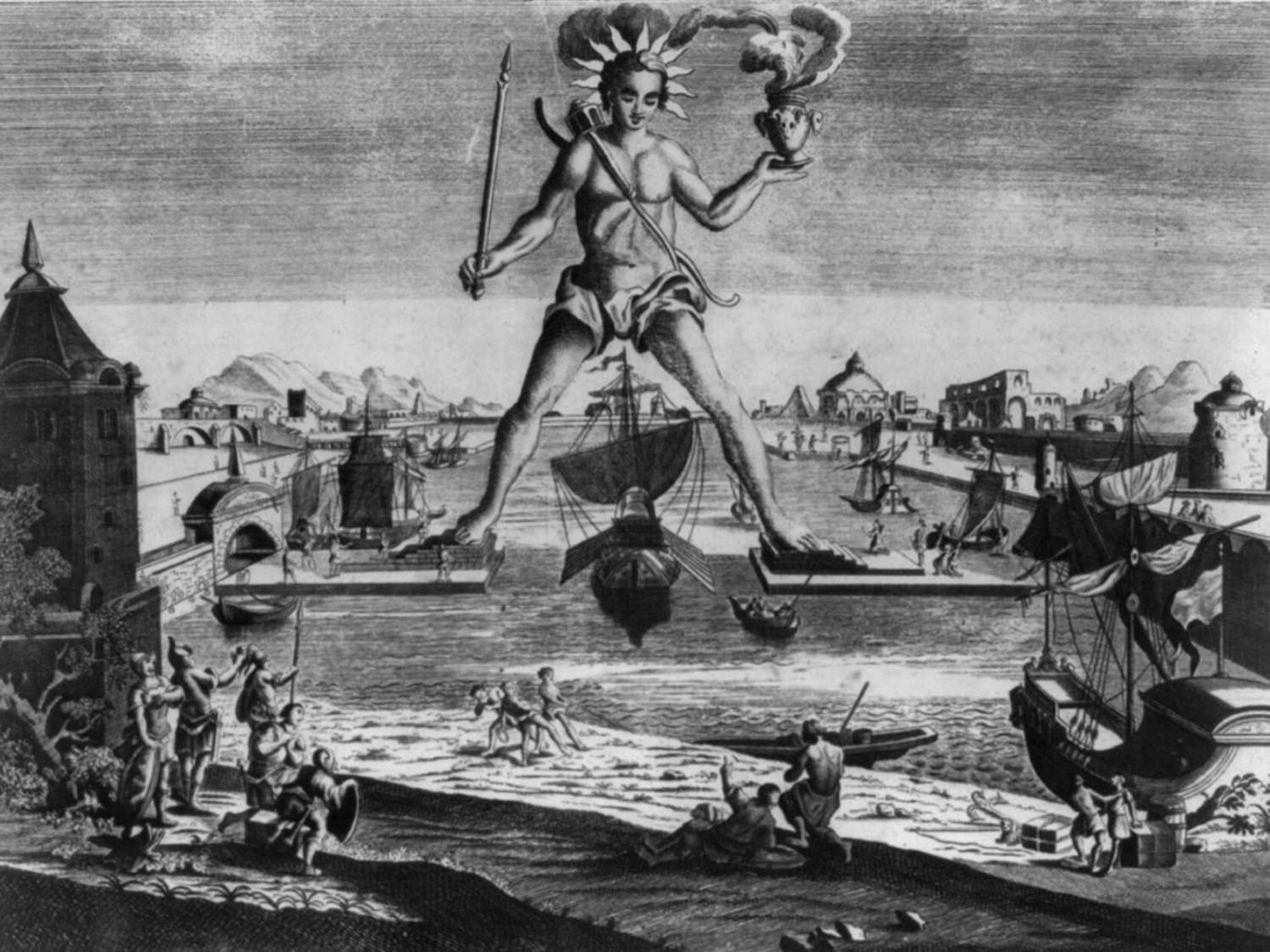

2. Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Hillah, Iraq

The beautiful Hanging Gardens of Babylon were planted in present-day Iraq, near the Euphrates river by Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II in 600 B.C… or were they? So many Roman and Greek authors mentioned the floral wonder in their literature that the royal garden at Babylon was sure to exist. Yet, these reports weren’t firsthand, and there’s no mention of them anywhere in Babylonian records to confirm their presence. It’s likely that the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were a widespread fictional legend, like Atlantis.

Allegedly planted for his lover who missed the greenery of her homeland, these accounts mention vibrant vegetation growing 75 feet in the sky on a terraced building or other structure. The engineering capability of the Hanging Gardens was entirely possible. If they did exist, the green space could have been watered through irrigation mechanics that carried hydration from the Euphrates up to the air. Recent evidence suggests that the gardens might have existed, but about a century later and through a different leader. Whether or not the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were a myth, it’s great fodder for the imagination.

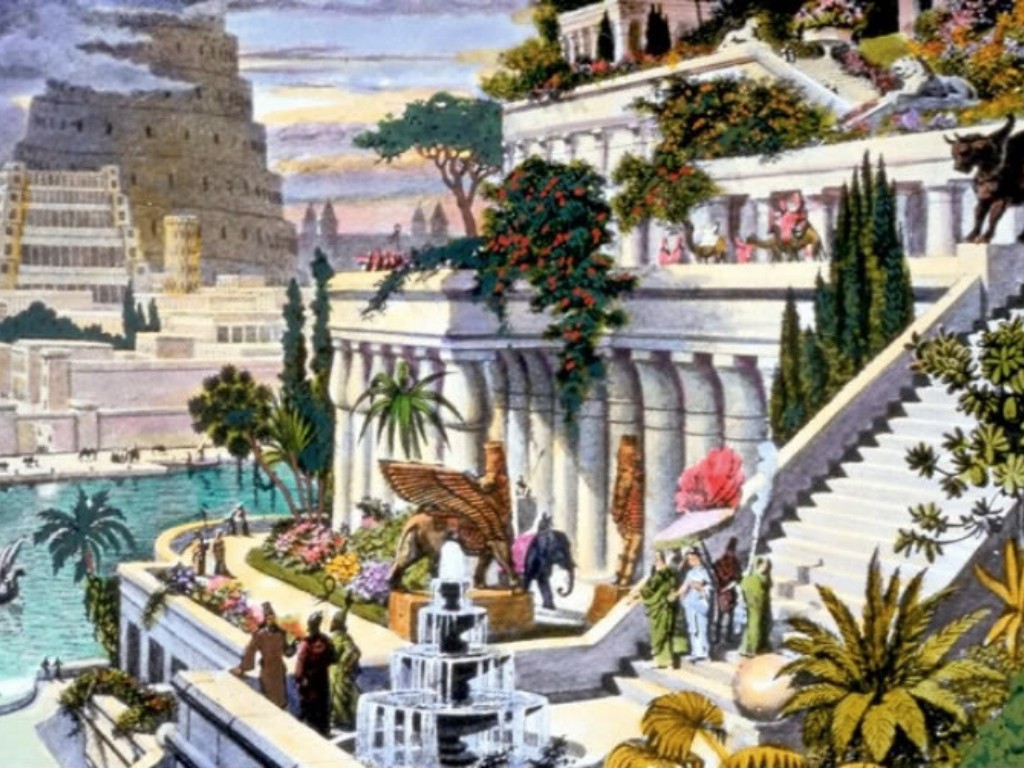

3. Statue of Zeus at Olympia

Olympia, Greece

Although the Statue of Zeus was likely destroyed in a fire in the 5th century, researchers are confident of its reality. It took 8 years for Athenian sculptor Phidias to erect the mammoth statue of the mighty Greek god. At its height, the statue was a sight to behold, almost too bold for the naked eye. Zeus, sitting in an intricate throne of cedarwood and precious stones at 40 feet, was gilded and inlaid with ivory. His left and right hands were occupied by a pointed staff and a statue of Nike, goddess of Victory, adding to his powerful representation. There’s no doubt that you would feel a sense of divinity and godliness in the same room as Zeus at Olympia, the temple where the ancient Olympics were held. It’s a true shame that we lost this masterpiece. Zeus sat on his throne for eight centuries until Roman conquerors closed the temple in 4 A.D. The statue was moved to Constantinople where it likely perished in a fire.

Fun Fact: Legend has it that Phidias asked the Statue of Zeus if he was pleased with the sculptor's work. As perhaps a sign of his approval, the temple was struck by lightning.

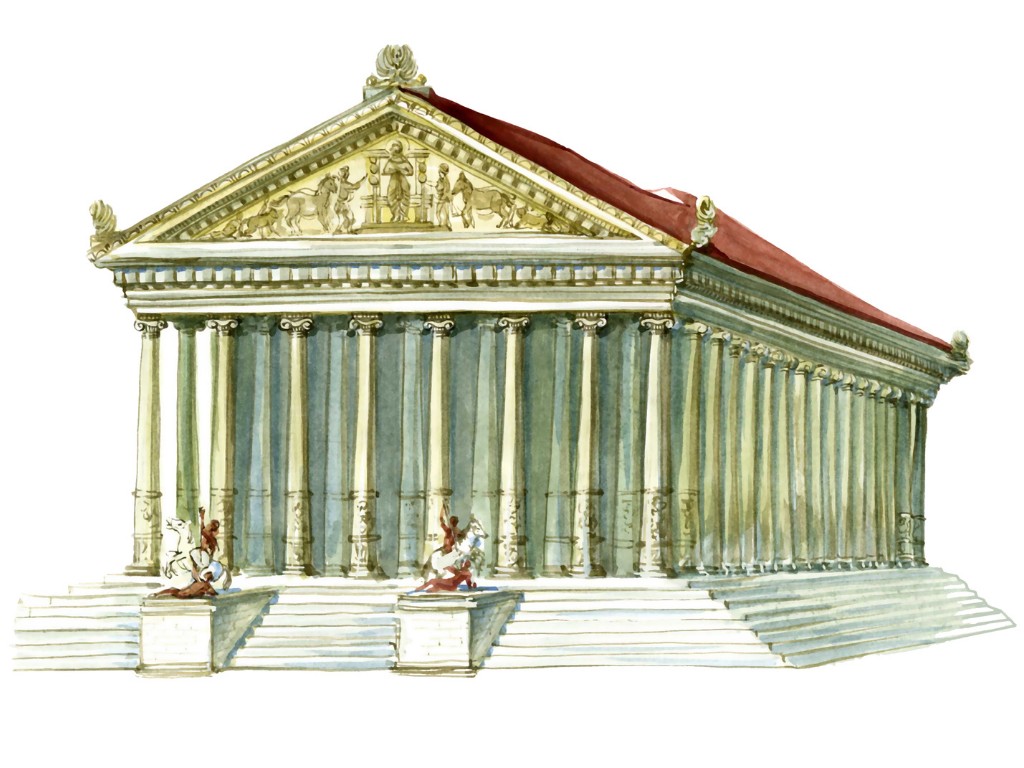

4. Temple of Artemis at Ephesus

Western Turkey

Unfortunately, this wonder of the ancient world was not fated to live on into the present. The Temple of Artemis was rebuilt many times only to be destroyed over and over again. A sizable temple at 350 feet by 180 feet, it was first built by Croesus, the king of Lydia, in around 550 B.C.E. in Ephesus, a Greek port city on the coast of present-day western Turkey. It was ornamented with gorgeous reliefs, statues, and other celebrated artworks. But the columned house may have been too beautiful for some to stand. In 356 B.C.E. (the night that Alexander the Great was born, some say), a man named Herostratus burned the famous temple down so he would be known to history. Herostratus certainly got his wish, but didn’t stop the ancient Greeks from building a second Temple of Artemis six years later. The second one, however, was met with demise after the invasion of Ostrogoths in 262 A.D. Fragments remain of the temple at the original site, and you can see some of the old columns on display at the British Museum.

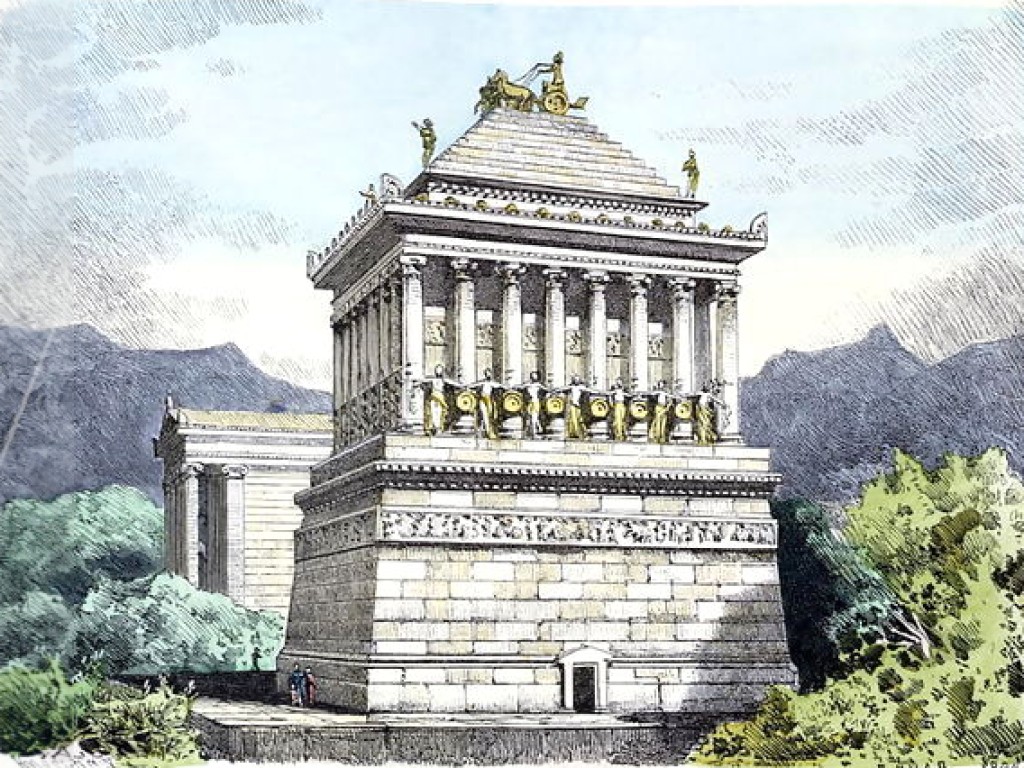

5. Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

Bodrum, Turkey

The word mausoleum is actually derived from Mausolus, the Greek ruler of Caria, for which the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus was built. After his death in 353 B.C.E, his wife, who was also his sister, commemorated his life with a tremendous tomb. What we know of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus as it stood in the ancient world comes from the many meticulous records and observations by Roman scholar Pliny the Elder, who died trying to save a family from the volcanic eruption at Pompeii. He wrote that Mausolus’ immense tomb spread across 411 feet, was surrounded by 36 columns, and was mounted by 24 steps leading to a sculpted horse and chariot. What’s more, the original mausoleum incorporated massive statues, incredible reliefs, and other artistic embellishments. It was likely an earthquake between the 11th and 15th century that reduced the mausoleum to mere crumbles. Like fragments of the Temple of Artemis, you can also check out a well-preserved frieze and other archaeological findings from the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus at the British Museum.

Fun Fact: Another interesting piece of lore for you — legend goes that his widow and sister Artemisia was so fraught with grief upon his passing that she drank a mixture of his ashes and water.

6. Colossus of Rhodes

Rhodes, Greece

Another devastating loss of art to an earthquake, the Colossus of Rhodes was a mammoth bronze statue of Helios, the sun god. It was molded over the course of 12 years by the Rhodians in 3 B.C.E. Sculptor Chares of Lyndus built the statue to commemorate Demetrius I Poliorcetes, the king of Macedonia from 294 to 288 B.C.E. Standing at 100 feet tall, gazing up at the eyes of Colossus’ colossal head was surely intimidating. Depictions of Colossus in later forms of art and in texts describe him holding a torch above a harbor’s bridge, one foot planted on one side of the bridge while the other was planted on the opposite side. This image is likely structurally impossible and only comes from portrayals during the Middle Ages. An earthquake around 225 B.C.E. caused the statue to plummet, and it lay fallen until 654 when Arabs invaded Rhodes, broke up Colossus, and sold the metal for scraps.

7. Lighthouse of Alexandria

Alexandria, Egypt

The pinnacle of innovation, the Lighthouse of Alexandria has been the blueprint for lighthouses ever since its construction in 270 B.C.E by the Greek architect Sostratos most likely for Ptolemy I. This ancient wonder was yet another one to be destroyed by a series of earthquakes between 956 to 1323, but was revered during its time. Based on its depiction on ancient coins, the lighthouse has three tiers, each magnificent on its own, but together create an outstanding layered tower. The first tier consists of a rectangular bottom, the second an octagonal pillar, and the top a cylinder where fire burned to warn ships on the Nile of the city’s harbor. A soaring 350 feet at its peak, only the Pyramid of Giza surpassed the Lighthouse of Alexandria’s height at the time.

Before its demise, the lighthouse may have gone through some transformations under different rulers. For example, Sultan Ahmed Ibn Toulou repurposed the site as a small mosque. Its ruins were also used to build a fort. In 1994, remains of the ancient tower were found in the Nile, including statues and stone sphinxes.

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World in Context

As eye-opening as these spectacles are, we must remember that Philo of Byzantium, who originally wrote these seven wonders, was biased. Like us, he was limited by the communication, dissemination of information, and technology of his time. Many of these ancient wonders are rooted in Greek, Roman, and Egyptian origins, civilizations that were very much involved with each other. What of other empires and civilizations? What secrets and wonders lie dormant from ancient peoples without a recorded history? We uncover some of these in the Seven Wonders of the Modern World, but many will remain lost forever.

Want to learn with a true expert? Get a comprehensive view with one of Context's tours, or learn more about your favorite destination or topic with our virtual, live-taught courses and seminars. If you want to dive deeper into the Seven Wonders, check out our The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World seminar with our expert on Ancient Greece, Dimitra Pilarino

Even More from Context

We're Context Travel 👋 a tour operator since 2003 and certified Bcorp. We provide authentic and unscripted private walking tours and audio guides with local experts in 60+ cities worldwide.

Search by CityKeep Exploring