On November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall—the final physical and symbolic vestige of the Iron Curtain—fell. As the whole world celebrated, the event was actually met with mixed emotion in Berlin itself. Initial excitement soured as Berliners began to realize that former neighbors had become “other.” In an attitude that is chillingly resonant today with the ongoing immigration and refugee crises across the globe, East Berliners were met with disdain and intolerance.

Shortly after the border between East and West Berlin was opened and travel between sides was once again allowed to all, the people that fought so hard and dreamed of the day the city would be reunited began to be bothered by trivial things about people from the ‘other side’, for example how ‘all those rude East Berliners flooded shops looking for bananas’.

Berlin’s History as Cultural Center

Prior to the Wall, from the beginning of the 20th century, Berlin had been a European center of intellectual, political, and artistic activity. Artist Oskar Kokoschka came here to conceive and write plays no less peculiar than his paintings, Christopher Isherwood wrote his Berlin Stories, Sigmund Freud visited to attend psychoanalytical congresses, and Albert Einstein rose to prominence.

In the late ‘70s and ‘80s, when Berlin started gaining a reputation as an underground legend, it was frequented by legendary polymath Joseph Beuys and musicians Iggy Pop and David Bowie, who could be found in Berlin’s dim smoky bars trying out new sounds.

Cold War Berlin

As Europe began to rebuild following the wreckage of WWII, Berlin was instead cleaved in two: East Berlin, under Soviet control, and West Berlin, an “island of democracy” deep inside East German territory. Construction of the Wall was commenced by the East German government in August of 1961, effectively cutting off West Berlin from surrounding East Germany, dividing families and even preventing some residents from getting to their jobs. The concrete barrier included guard towers, a "death strip" of anti-vehicle trenches, and other defenses.

While the Wall was standing, several thousand people successfully defected to West Berlin. And it’s reported (although the number is disputed), that several hundred East Berliners died in their attempts to make the crossing, either shot by German Democratic Republic (GDR, the East German government) officers or as result of attempts to escape by tunnel, aerial wires, and other extreme measures.

Over the course of the time that the Wall stood, East and West Berlin developed independently. That divide can easily be seen in the architecture of the “two cities.” While East Berlin reflected Communist ideals with monumental architecture focused on centralized power, West Berlin embraced modernist buildings and green space to emphasize the values of freedom, individuality, and the non-authoritarian order of democracy.

The Fall of the Wall

Finally, on November 9, 1989, following mounting political pressure, the checkpoints were opened. Crowds from West and East Berlin jumped atop the wall to celebrate the pivotal world event, for the Iron Curtain was no more. While November 9 marks the official fall, the dismantling of the wall took place over a long period of time, with the GDR military beginning demolition in June of 1990.

Here's a firsthand account of that night from Context historian Chris, who was an East Berliner at the time of the fall:

Something had happened, but we did not know what. When my aunt called, we became part of it. She said she had watched the news and that it appeared as if the authorities of the GDR were about to open the checkpoints that very night for us East Berliners to be able to go into West Berlin...It was confusing. It was exciting. Some of us went that very night, some of us went the next day…and we celebrated for weeks. We celebrated the fact that after months of protest finally something was changing. There was movement in an all too rigid system. What it really meant we could not tell, but we knew that on that Thursday night our world was turned upside down and our lives were changed completely.

More than a physical barrier

The dismantling of the wall extended beyond the work of hammers and chisels—Berlin also had to find a new identity. After thirty years of separation, East Berlin and West Berlin had each developed a distinct culture and values. Again Chris, who herself was born in the GDR, reflects:

For me as a child, the Fall of The Berlin Wall meant being part of a historic moment–everyone was talking about my city and masses of people came to see it. It also meant that many options were added to my future path, and that the content and values of my life were redefined. For my parents the Fall of The Wall mostly meant insecurity. Would the checkpoints close again? They did not. Would they be able to keep their jobs? They did not. Would everything they believed in and had built up (for generations) be secured and reformed with caution? It was not. Would they be allowed to help shape this new society? They were not.

All of a sudden we were allowed to watch Western TV, although it previously had been clearly marked as the enemy’s infiltrating capitalist propaganda. We were invited to spend our money on Western items that no one knew how to use or really needed. We began to learn history from a Western perspective, what we had learned before was forcibly erased from the public sphere, and it was strongly encouraged to be forgotten.

People from the East realized more and more that they were being treated as the losers of history and that united Germany was to be defined by others. Their input was not welcome. Their belief system was fundamentally wrong. Their economy could not be saved. Bitterness and frustration set in, and is still remarked upon daily in some families of “the new provinces."

While the physical structure of The Wall is long gone, people walk around with a wall in their heads and they define themselves as East or West Berliners. There is still social segregation, there are very different election results in the East and in the West. And there are (seriously!) people that wish The Wall would come back. We call it Ostalgie, nostalgia for East Germany.

Despite the ongoing struggles to integrate East and West, that tension resulted into the unique Berlin that visitors see today. Shortly after the fall of the Wall, in the early ‘90s, deserted areas adjacent to both sides of the former border were occupied by alternative musicians, radicals from art and politics, and punks. It was then and there that the unique Berlin spirit was conceived and hammered out—a carefree, adventurous, live-and-let-live affair among the riches of the Baroque and Neoclassical palaces and Soviet-style monochrome apartment blocks. The artistic fervor of the city immediately following the fall of the Wall can be seen in the multitude of museums—from the giants of Museum Island to lesser-known gems—and over 300 established contemporary art galleries. (You can check out Berlin’s contemporary art scene on a walking tour of Auguststrasse, the core of the 1990s Berlin art scene.)

Berlin today

Now, thirty years on, the city is still seeking out its sense of self. Ask locals what Berlin is about and they’ll mention early morning walks home over the Oberbaum Bridge, gazing at the sun’s first rays bouncing off the TV Tower’s tip; they’ll tell you about Berlin’s empowered local communities, or Berlin’s späti culture, which actively encourages social engagement through street-side beer swilling. And Berlin also overflows with rich cultural history with sprawling spaces like Museum Island, and has a world-class repertoire of independent artists and music initiatives.

Just as important are the many memorials dedicated to the Wall and WWII in Berlin serve to remind people of a divided time and prevent the return to a troubled past. As the capital of Nazi Germany, sites like the Topography of Terror Museum and the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (both featured in our Nazi History Tour) are as affecting as they are important. And of course, the Berlin Wall itself is essential to understanding not only to the fabric of Berlin, but to the world.

30th Anniversary celebrations

This year, in commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the event that changed the world, Berlin is holding a week-long festival across seven locations important to the Peaceful Revolution.

Touring the Wall

Even beyond the anniversary events, the Berlin Wall can be visited year-round. Here are our tips for how to visit the Wall.

In honor of the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, we’ve organized a two-day experience that traces the history of the Wall’s footprint in both Berlin and Potsdam. Led by historians, we will investigate the end of World War II, the Cold War and the reality of life before, during, and after the Berlin Wall.

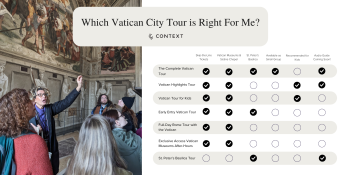

Other options with Context include our 3-hour Berlin Wall tour, our Berlin Wall for Kids tour, and a Berlin Wall bike tour. And while you’re in the city, don’t forget to check out all of our Berlin tours.