The History of Fascist Architecture in Rome

A view of the Santi Pietro e Paolo church in Rome, a classic example of Italian fascist architecture.

Architecture and urban planning played a key role as both propaganda, and as a tangible manifestation of Mussolini’s fascist ideology. Mussolini didn’t simply build buildings or put up posters to reflect his, and by extension Italy’s, might (though he did do plenty of that as well); fascist architecture in Rome was a balancing act between glorifying the Ancient Romans to whom all modern day residents remain beholden and espousing a stark new vision for modernity. While some of his actions with the longest-lasting impact were rooted in city planning (the construction of the Via della Conciliazione and Via dei Fori Imperiali, namely—large boulevards created to glorify St. Peter’s and the Colosseum by creating a direct, wide-reaching thoroughfare at the expense of a host of historical structures demolished in their wake) and archaeological digs meant to demonstrate the power of ancient Rome like Ostia Antica and Circo Massimo, fascist architecture in Rome—namely, that of the EUR (explored on our EUR Tour) remains a lasting legacy and point of fascination to this day.

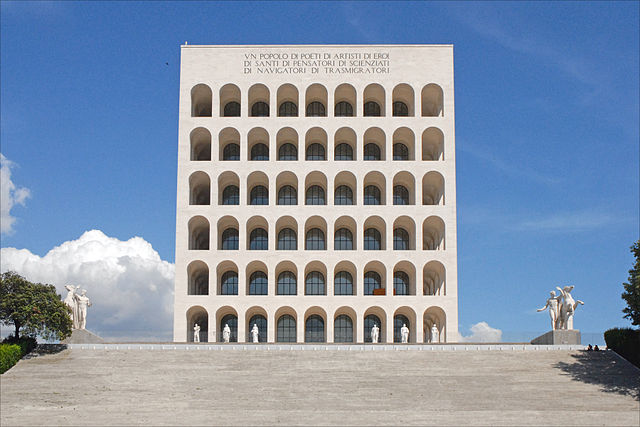

The Italian Fascist style associated with buildings constructed during Mussolini’s era evolved from Futurism and Rationalism combined with Italy’s perennial reverence for ancient Rome; ironically, while they collectively provided much of the aesthetic framework for fascist architecture in Rome, they differed quite a bit in ethos and implementation, tugging buildings of the day in different directions resulting in a fascinating middle ground. While Futurism, a style that emerged from Italy, emphasized speed, modernity, and an outright abandonment of what came before, much of the most notable Roman fascist architecture is heavily indebted to classical architecture (like the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, colloquially referred to as the “Square Colosseum”). Meanwhile, Rationalism seeks to provide a logical, scientific basis for architectural decisions, often working as an intermediary between the two wildly differing styles. Thus, Roman fascist architecture became something of a modernist-classical hodgepodge, incorporating classical elements—travertine marble, statuary, scale, proportion, aches, columns, loggias—with clean lines and modern minimalism.

Today, fascist architecture in Rome inhabits a strange role in its civic and national identity—unlike Germany or Argentina, the remnants of this deeply regrettable era in Italy’s history have largely not been condemned as icons of fascism, but have instead been championed by fans of modern design (and, more disconcertingly, have become rallying points for a rising contemporary Italian fascist movement; Mussolini’s tomb in Predappio in particular has become a site of pilgrimage for right wing Italians). However, with this renewed interest has come some pushback from the Italian left; Predappio’s liberal mayor has proposed a Museum of Fascism to examine Mussolini’s era in a more critical light, and the excellent Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah has opened its first exhibition in the small, northeastern town of Ferrara near Bologna.

Want to learn with a true expert? Get a comprehensive view with one of Context's private or small group tours in Rome, or learn more about Italy with our online lectures.

Other Blog Posts You May Like:

Even More from Context

We're Context Travel 👋 a tour operator since 2003 and certified Bcorp. We provide authentic and unscripted private walking tours and audio guides with local experts in 60+ cities worldwide.

Search by CityKeep Exploring