12 Eiffel Tower Facts You Never Knew

La Tour Eiffel, or Eiffel Tower—perhaps the most famous symbol of Paris

The annals of art history are littered with tales of once-reviled artists and artworks that became masterpieces—Picasso was dubbed satanic, Cezanne a madman, Van Gogh a loon. One perhaps lesser-known turnaround story is that of Paris’ Eiffel Tower: somewhere in the past 126 years, the monument went from the city’s most abhorred structure to one of its most beloved.

There’s no ignoring that the Tower has become an international symbol of not only Paris, but of France as a whole. In the many years of its existence, it’s only natural that the iconic landmark has gathered plenty of tales to tell the curious traveler.

And who better to tell these tales than one of Context’s own experts on Parisian history, Gil Soltz. Having lived, written, worked, and led tours in Paris for over a decade, this knowledgeable scholar has given us an incredible list of facts you might not know about the Eiffel Tower.

Read Gil’s brilliant little known facts about this wondrous structure, and then join him on a half-day tour of Paris for even more insights on the City of Lights.

1. Gustave Eiffel Bought the Eiffel Tower Design Plans

You may already know that Gustave Eiffel, the Tower’s namesake, famously won a competition to build the 1889 Exposition Universelle centerpiece, but the design was not actually his own. Two young engineers, Emile Nouguier and Maurice Koechlin, approached Eiffel with a basic idea for a tower. After a few alterations, Eiffel decided to purchase the plans from these engineers, enter them into the competition, and build the iron construction that would forever cement his legacy.

2. Gustave Eiffel was a World-Renowned Engineer

While Gustave Eiffel is now known for the building in Paris, back then he was a world-renowned structural engineer, widely recognized for his use of metal. Eiffel had built more than fifty wrought-iron bridges and viaducts in France alone, as well as a large amount of projects overseas in French colonial outposts (Peru, Saigon in Vietnam, and Shanghai, China). He designed easy to assemble modular railway bridges, which made them ideal for the far flung colonies.

Furthermore, he was the celebrated engineer of the world’s highest railway bridge in Garabit, France, which stands at four-hundred-foot-high iron arches. Other acclaimed projects of his include the Nice Observatory and even the interior skeleton of the Statue of Liberty.

So, really, the 1889 Exposition Universelle competition wasn’t all that fair to other contestants. They didn’t stand a chance!

3. Gustave Eiffel Personally Funded Most of the Tower

It would cost about 30 million euros if the Eiffel Tower were to be built today. When the Tower was built, the government offered to fund a mere 18% of it, leaving Eiffel to personally raise the rest of the money. Originally, the tower was meant to be a temporary structure for the duration of the World’s Fair. However, to attract investors, Eiffel arranged to keep the tower up for twenty years, during which time he could take all the profits from entry fees and restaurant concessions. Eiffel had all of his debts paid off within a mere six months!

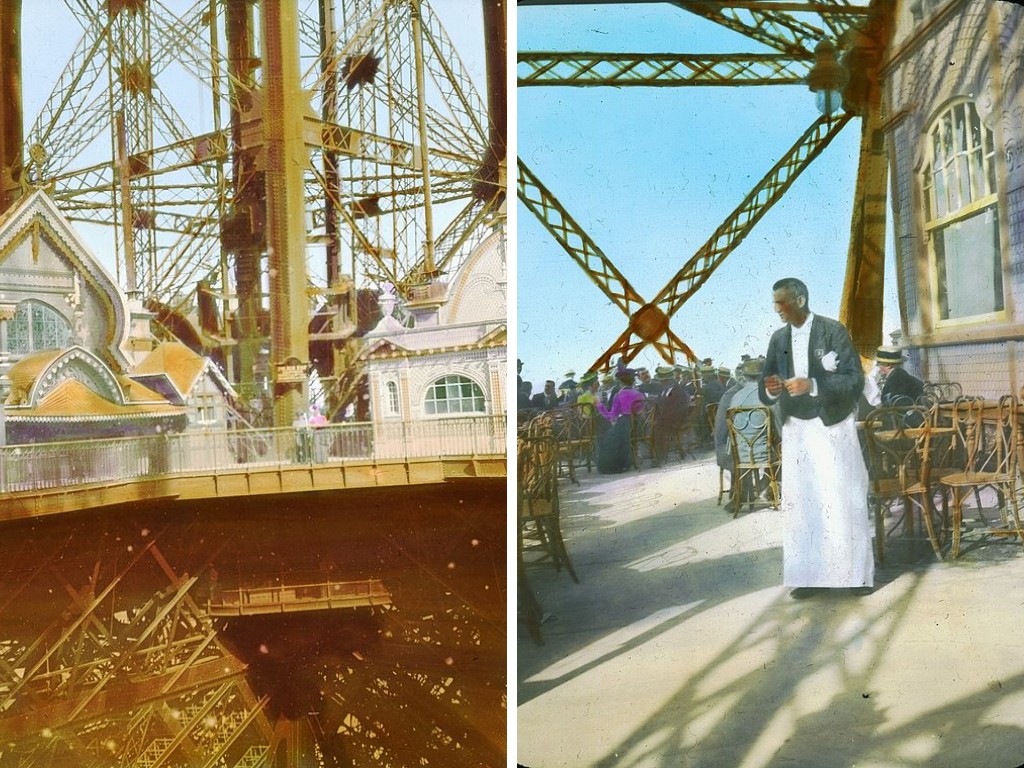

4. There were restaurants on the first platform.

Since the Tower was designed to be an entrance way to the Universal Exposition of 1889, the first platform had four eateries: an Anglo-American bar, a Flemish brasserie, and then a Russian and French restaurant — each with five or six hundred seats. The restaurant and reception spaces have been renovated many times since then.

5. Negative space makes the Tower unique.

For all you lovers of art and architecture, this fifth point is more of an appreciation for the Eiffel Tower’s beauty. Its opposing characteristics is exactly what makes it such a striking figure. At once weightless and heavy, the soaring tower looms above us in all of its contrasting glory. The architectural wonder incorporates as much void as it does metal, and its usage of negative space is just as important as its usage of iron.

6. The Eiffel Tower moves in the wind and from heat expansion.

The highest point on the Tower sways at an average of 2.5 inches in high winds. Not only that, it also moves from the heat of the sun expanding the metal! No need for concern, however, the amount of movement is minuscule for a tower of this size.

7. There used to be a small newspaper printing press on the second floor.

When Eiffel completed the first level he invited eighty of Paris’s most influential journalists to a summer banquet served on the tower’s first platform. Le Figaro, the oldest national newspaper in France, praised the tower and made a deal to have a tiny editorial office and printing press on the second floor, producing a special daily paper: Le Figaro de la Tour.

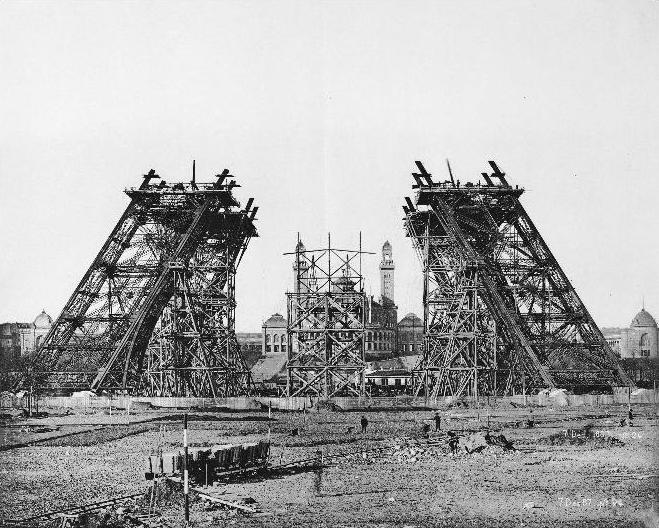

8. There was employee unrest when building the Eiffel Tower.

On a number of occasions constructors protested the heights in which they had to work, the meager pay, and the cold conditions. Eiffel tried to resolve employee discontent by promising a 100 franc bonus to all who worked until the building’s completion. Gustave didn’t play games either. He threatened to dismiss and replace anyone who didn’t show up to work.

9. The emblematic French landmark isn’t 100% French.

Although the Fair Commission stipulated that the Eiffel Tower would have to be a completely French invention using only French labor, materials, and technology, the elevators were furnished by the Otis Elevator Company of New York. Widely recognized as a feat of engineering at the time, the elevators introduced the concept of the counterweight lift, in which two elevator cabs operated as a pair in each of the Tower’s pillars: when one cab went up, the other came down.

10. The Tower was saved from being torn down by its antenna.

In 1909, Gustave Eiffel’s contract expired, and the public wasn’t as enthusiastic about the Tower. The public began to wonder about its practical purpose, and Gustave tried to persuade them about its usefulness in meteorology, aerodynamics, telegraphy, and even military strategy. From his private apartment on the Tower, he conducted experiments with the weather and dynamics of the wind to prove the structure's worthiness. Eventually, France decided to keep the Tower because of its value as a radio beacon.

11. A conman tried to sell the Eiffel Tower (and it worked).

In 1925, the con artist Victor Lustig “sold” the Eiffel Tower for scrap. Posing as a government official, Lustig convinced a group of metal dealers that, given the expensive upkeep of the Tower, the city had decided to sell it for scrap. One dealer fell for the con, and not only paid Lustig for the Tower, but also gave him a healthy bribe on top of that. Lustig then hastily took a train for Vienna with a suitcase full of cash, escaping from law enforcement. In the end nothing happened because the man who purchased the Eiffel Tower was too humiliated to complain to the police.

12. An American woman married the Eiffel Tower.

In 2007, Erika Eiffel actually "married" the Eiffel Tower in a commitment ceremony in 2007. She is the founder of OS Internationale, an organization for those who develop objectophilia, or attach significant relationships with inanimate objects. She first encountered the Eiffel Tower in 2004 and felt an immediate attraction.

A native of San Diego (USA), Gil graduated in Politics and English from Brandeis University and later earned two Master's degrees: the first in Public Administration from New York University, and the second a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing. After earning his MFA and producing his first book, Gil moved to Paris for a Parisienne and hasn't looked back. For ovefr a decade Gil has lived, written, worked, and led tours in Paris. His background in literature - both canonized and contemporary - combined with his understanding of the inner workings of cities have enabled Gil to tell his narratives as experiences and provide unique insights into Parisian life.

Want to learn with a true expert? Get a comprehensive view with one of Context's tours, or learn more about your favorite destination or topic with our virtual, live-taught courses and seminars.

Other blog posts you may be interested in:

- 36 Hours in Paris

- Vive la France: Bastille Day Now and Then

- Guide to French Wine Regions

- A Guide to Visiting the Louvre Museum in Paris

- Landmarks of Paris

Even More from Context

We're Context Travel 👋 a tour operator since 2003 and certified Bcorp. We provide authentic and unscripted private walking tours and audio guides with local experts in 60+ cities worldwide.

Search by CityKeep Exploring