Beyond the Brandenburg: An Expert’s Guide to Berlin's Unseen History

An aerial view of Tiergarten in Berlin

By: John Owen

Berlin is a city famous for its history. Almost to a fault.

For visitors to the German capital, the city’s most famous sights–the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag and the Holocaust Memorial–are “must sees.” But all three of these most famous sights sit within around 300 metres of each other. What makes Berlin such a fascinating place to visit is the ubiquity of its history even in the most unexpected places.

Today, I’ll show you around–virtually, of course–some of the sites that a lot of visitors miss, including an extremely important part of history that lies just beyond my very own doorstep. Let’s explore, shall we?

The Tiergarten's Hidden History

Within the centre, and around famous sights, the layers of history reveal themselves if you look hard enough. Take Berlin’s biggest park, the Tiergarten, for example. It sits just to the west of the Brandenburg Gate and is bordered by lots of the city’s other most famous landmarks.

Tiergarten Park, Berlin

Tiergarten Park, Berlin

The park’s usage has changed over time from being the Prussian royal family’s hunting grounds to becoming a public park just outside the city walls in the 18th century. It was very late in history–1920 to be exact–that the Brandenburg Gate ceased to mark the formal limit of Berlin. Within 30 years, it would return to sitting on the edge of a city, this time in East Berlin with the Tiergarten acting like a kind of buffer zone on the edge of West Berlin.

If you walk around the Tiergarten today, you are likely to be impressed by its bucolic beauty. Heavily forested, it is a habitat for a vast number of rabbits and the goshawks that prey on them, while in spring every year its small copses emanate the distinctive call of nightingales. It is in many ways a surprisingly natural place amidst the artificiality of a modern city. However, should you look closer, you will see that there are essentially no old trees across the park. You will be able to wrap your arms around the vast majority. For a park that has existed for close to 500 years in a country with a deep romantic attachment to forests, this is somewhat surprising.

Tiergarten Park, Berlin

Tiergarten Park, Berlin

But as it so often happens in Berlin, there is an answer in the city’s traumatic 20th-century history. Allied bombing and the felling of trees for firewood during the war and its immediate aftermath led to the deforestation of the park. Indeed the park was so devoid of trees for a while that the British (in whose occupation zone it fell) turned large tracts of it into farms for Berliners to grow food. As a result, it was only really “reforested” in the late 1940s with different sections taken on by different West German cities. Without looking at the trees, it would be easy to miss these additional layers of Berlin’s history.

History on the Wannsee

Almost every corner of Berlin has an interesting history. Sometimes this can be jarring. Out on Berlin’s western edge, the huge Wannsee lake stretches out with sailors and swimmers enjoying its waters in the summer. Tucked away in the forest surrounding it is the shooting club which housed the 1936 Olympics shooting events.

But the name of this lake is generally known for a much darker event that happened here. On 20 January 1942, a group of senior Nazi functionaries and civil servants met in a villa on the lake where, over the course of just 90 minutes, they discussed the logistics for the genocide of Europe’s Jewish population. This was cryptically referred to as the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question.” This lakeside villa is now a memorial museum, which you can visit.

House of the Wannsee Conference

House of the Wannsee Conference

Just a few hundred metres down from the villa, there is a grim reminder of the consequences of this genocide. In the very same row of villas on the lakeshore sits a house that once belonged to the great German Jewish painter Max Liebermann. He was so successful by the early 1930s that he lived in a building right next to the Brandenburg Gate. Liebermann died of natural causes in 1933, but his wife Marthe committed suicide in 1943 once the threat of deportation to Theresienstadt concentration camp became concrete. A couple of plots further down, two oars stand outside a rowing club in memorial to the Jewish members murdered during the Shoah.

Divisions on the Glienicker

There are not many cities which have these kinds of jarring juxtapositions as part of their normal life, and it is one of the reasons Berlin is so compelling. Just a short distance from Wannsee is another, less well-known, Berlin lake–the Glienicker See. It and its near neighbour, the Sacrower See, are two of the best lakes to swim in in the whole city. Swimming in lakes is very much part of life in Berlin, and (although the vast majority of tourists don’t do it) should be seen as an essential part of any trip to the city.

If they live near enough today, Berliners will make weekly - even daily - trips out to lakes in the summer. However, for 27 years, families on the western side of the Glienicker See (which confusingly was part of East Germany while the eastern side belonged to West Berlin) could not access its water. The Berlin Wall ran along its shore, and the second “internal” wall coursed through their gardens.They would hear the shouts of West Berliners enjoying the water but could not partake themselves.

The Wall

The Wall

For some years, I worked as a historian and guide at a house on the Glienicker See. Built by a German-Jewish family in 1927, it has recently been restored by their descendants (now largely Brits). Over my time working there, I was lucky enough to conduct interviews with people who had experienced the lake from both sides.

One West Berliner told me he had learned to windsurf on the lake using the border buoys (the border actually ran through the middle of the lake) as a good way to train his skills in straight-line surfing. If he made a mistake, he would occasionally hear a warning shot from the border guards.

The Glienicker See

The Glienicker See

Another insisted (although I barely believe him) that his yearning to enjoy the water became so great that he once succeeded in scaling the Wall, swimming across to the western side, having a beer and returning. For people like this the Wall was not just the obviously geopolitical boundary between two political systems - it was a part of their daily life; and one that was ripe to be mocked or played with.

Explore the History Hiding in Wedding

On another level, little places in Berlin can often tell big stories. I live in an area of Berlin called Wedding, often referred to as “red Wedding” for its leftist politics. You are unlikely to come here as a tourist on your first visit, but were you to do so, you could tell a good part of the story of twentieth socialist politics in Berlin within about a 20-minute walk of my front door.

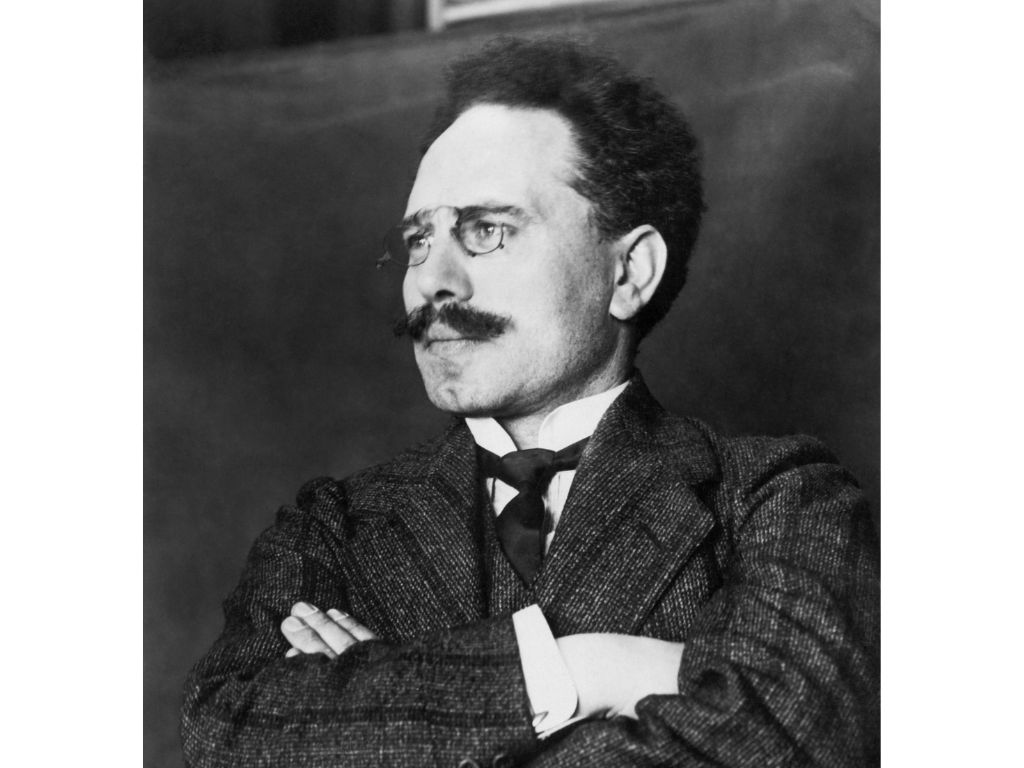

Karl Liebknecht

Karl Liebknecht

Just a few hundred metres away sits a building previously donated to the great German socialist thinker Karl Liebknecht. (Members of Parliament were previously required to own land to hold their government position.) Liebknecht was an idealist and revolutionary who was murdered in the aftermath of World War One. He never lived to see a socialist state be attempted in Berlin, but someone who grew up very near his former house did.

The man who would go on to be head of East Germany’s repressive secret police, Erich Mielke, grew up just a short walk from Liebknecht’s house. His Berlin was a violent one where political ideas clashed in street fights around the streets of northern Berlin. A few years later, when socialism had won at least part of the fight for the city, the Wall he and his colleagues planned cut him off from the very streets where he had come of age, both literally and politically. .

The Start of the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Not only did two of the most important figures in its history live in this area, but on 9 November 1989 at a border crossing between Wedding and an area in the east called Prenzlauer Berg, the same Wall opened for the first time - just a few minutes walk from where Mielke grew up. East Germans began swarming across into the West in a party mood, greeting an end to the reign of terror his secret police had held over their lives.

A plaque marking the site of the Berlin Wall

A plaque marking the site of the Berlin Wall

Today, little marks the spot where one of the most momentous events in the twentieth century happened. If you did not know, you would probably pass by without a glance. There are a few placards, but most of what was once the border crossing point is taken up by a Lidl supermarket–an example of where history in Berlin sometimes has to give way to the practicalities of modern life.

Surprising Ties to Japan

If you were to walk down the steps by this supermarket, you’d find yourself on a path lined with cherry trees. Again, trees in Berlin can act as a relatively tacit key to the history. This grove of cherry trees comes alive in the spring with beautiful pink blossoms.

Japanese Cherry trees near the site of the fall of the Berlin Wall

Japanese Cherry trees near the site of the fall of the Berlin Wall

It is about as close to getting to the Japanese sakura season that you will get in Berlin. And the connection to Japan is real–these trees were donated by viewers of a Japanese TV programme who wanted to give Berlin something to celebrate the fall of the Wall.

Discover Berlin’s Layered History

Berlin is a place dripping in history, much of it very recent and extremely traumatic. At the same time, it is simultaneously a great fun, liberal, cheap, and buzzy modern city. This stark contrast is something Berliners get used to, but it makes it a fascinating place to visit.

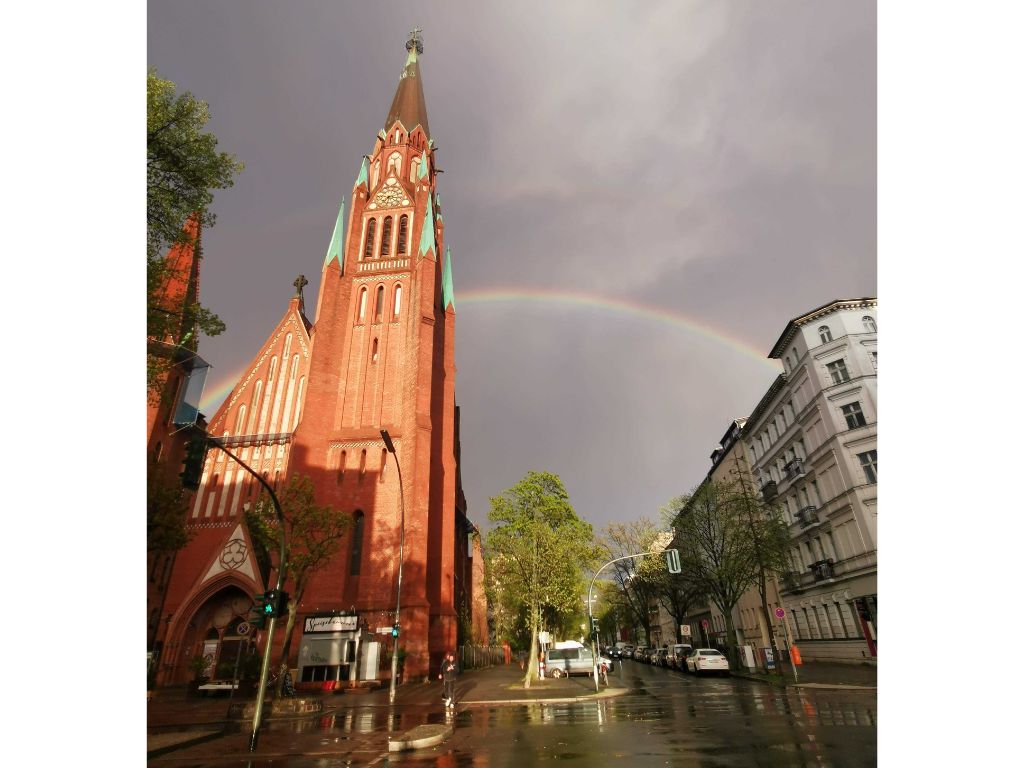

A wash of color after a rainfall in Wedding

A wash of color after a rainfall in Wedding

And if you stop to look around, almost every feature on the map has a story to tell. So I invite you to come and experience this complex and constantly confounding city. Enjoy its famous corners but make sure to explore and find some of the city’s hidden trauma and hidden treasures. Sometimes you have to turn on your radar to find the myriad of ways that history appears in even the most unlikely places.

About John: John studied History and German at the University of Oxford, eventually specializing in German-Jewish history and the history of the Third Reich. He started visiting Berlin as a teenager and eventually moved to the city permanently. He now resides in Wedding, a suburb of Berlin. The tangibility of history in Berlin and Germany, especially that of the twentieth century, never ceases to thrill him.

Even More from Context

We're Context Travel 👋 a tour operator since 2003 and certified Bcorp. We provide authentic and unscripted private walking tours and audio guides with local experts in 60+ cities worldwide.

Search by CityKeep Exploring